An Inglewood Charter School Looks To Literacy To Build Success Among Its Black Students

Marques and Stacey Gunn have seen their sixth grader daughter Brooklyn’s love for reading flourish since joining Wilder’s Preparatory Academy last school year.

-

EdSource, an independent nonprofit organization founded in 1977, is dedicated to providing analysis on key education issues facing the state and nation.

She even lined her Christmas wishlist with several books recommended by her English teacher and quickly devoured them.

“Her interest in reading and research has grown so much since being at Wilder’s,” Stacey Gunn said. “It’s amazing to both of us.”

Wilder’s Preparatory Academy in Inglewood is showing unusual success in teaching literacy and math. The K-8 school enrolls a student population that is more than 85% Black and boasts test score results that reflect performance far above that of the state average for all schools regardless of racial composition.

In fact, the scores make it the top performing school among predominantly Black schools in the state. It’s also a bright contrast to the performance levels reflected among the rest of the state’s Black student population, which is ranked lowest in performance levels among all of California’s racial and ethnic groups.

-

At magnitude 7.2, buildings collapsed

-

Now spinning in front of Santa Monica apartments

-

Advocates seek end to new LAUSD location policy

In California, 30% of Black students met standards in English language arts in 2022 and 16% in math. Both rates are 17 percentage points below the results for all students statewide.

But at Wilder’s Preparatory Academy, 72% of elementary and 82% of middle schoolers met standards in English language arts and 51% of elementary and 46% of middle schoolers in math. The scores surpassed the performance of surrounding Inglewood Unified by more than double in both subjects.

“Many people ask, ‘What’s the secret sauce?’” CEO and administrative director Ramona Wilder said. “Really, it’s a mindset.”

Wilder’s Preparatory Academy is a school of nearly 600 students that was started by Wilder’s late father, Raymond. The Wilder family comes from a long line of Black educators tracing back to the 1800s when the family converted an old church building into a schoolhouse and taught freed slaves how to read, Wilder said.

Her parents’ presence in Inglewood education began with a private preschool and, later, elementary school, before transforming into the now publiccharter school in 2003 in an effort to be more accessible for families.

At Wilder’s Preparatory Academy, nearly 70% of students are on free or reduced lunch because of their families’ low income. Students are accepted to the school by lottery off of a waitlist.

Myrna Castrejón, the president and CEO of the California Charter School Association, said Wilder’s Preparatory Academy’s success shows what is possible when goals are clearly outlined and followed up. Its flexibility as a charter just makes that easier, she added.

Because they are independent, charters don’t have to adhere to specific district standards, but students are required to take the Smarter Balanced assessment, California’s statewide standardized test.

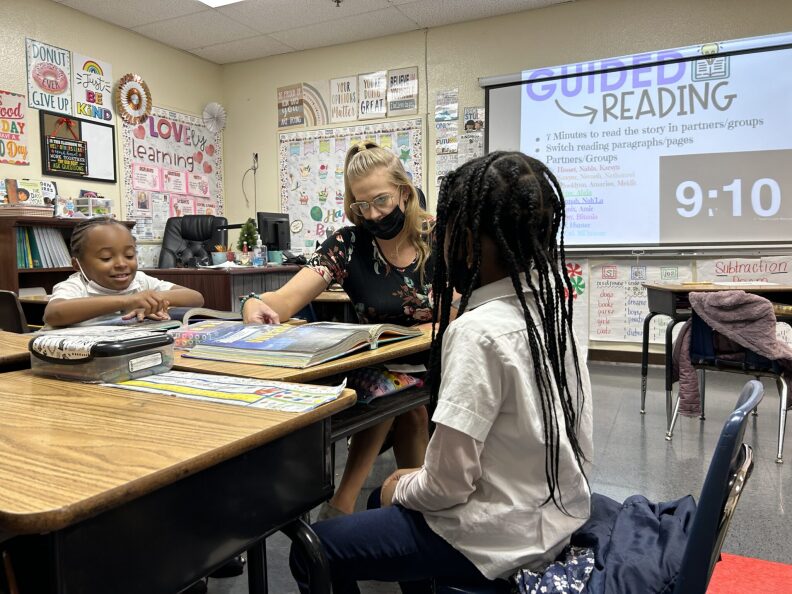

The school places a heavy emphasis on intervention for students who need extra help. Teachers pull students out during the school day to work on skills, and tutoring is available after school and on Saturdays.

“This is a labor of love,” Castrejón said. “This is a place that was created with intentionality, with design that looks well beyond just the question of resources and programs.”

Castrejón said she believes school districts and other charters can look at Wilder’s Preparatory Academy as a model, particularly by treating Black student education with intentionality.

“I also don’t want people to believe that just because Ramona Wilder is special nobody else can be Ramona Wilder,” she said. “This is a call to action to us. This can be done by others. This is an invitation for us to stop dithering around excuses for why things can’t be done.”

UCLA education professor Tyrone Howard agreed that Wilder’s effort could be a model for building strong literacy skills, but that it’s also important to remember that each school is unique.

“I don’t think it really is rocket science at the end of the day,” Howard said about the possibility of applying similar approaches in public schools. “It’s just, do we have the capacity and the skills and the resources to make sure that it happens early on? Even in pre-K, how are we making sure that that foundation is in place and you build upon it.”

The importance of a strong foundation is something that the Gunn family agrees with, particularly following Brooklyn’s transition to Wilder’s from a private Christian school in Long Beach. They said they were happy to see a sense of caring, higher level of accountability among students and higher academic standards. It took Brooklyn a little time to get used to it, but they said they’ve seen her become more goal-oriented since.

“In the beginning she had some late nights, she’d be up to 1 o’clock in the morning doing homework, you know,” Marques Gunn said. “Some crying initially and things like that, but she figured it out.”

Brooklyn has been developing an interest in engineering and astrophysics through her academic explorations, according to Marques Gunn.

Across Wilder’s Preparatory Academy, teachers aim to have its students reading and writing proficiently in kindergarten rather than by third grade. Early grades focus on honing phonics and comprehension skills through the Wonders ELA curriculum, which is among the curriculums that emphasize phonics and the science of reading.

In Yvette Fenton’s second grade class, students slide their fingers over a paragraph on the life of 1920s pilot Bessie Coleman as a class. They paused only to debate unfamiliar words like “aviation,” which they sounded out together with Fenton and then shared ideas about its meaning.

“What would make sense? What could that be?” Fenton asked her students.

Those literacy efforts are integral to Wilder’s Preparatory Academy’s educational foundation, according to Wilder and the school’s teachers.

“When a child struggles with reading, it can inhibit how they actually learn,” said third grade teacher Mary Clemmons, who has been with the school for decades and has also taught kindergarten. “It can inhibit how they want to react in class or if they’re engaged in class. Reading takes place across the curriculum. And so for us to build those critical thinking skills, reading must be the foundation.”

For Wilder’s Preparatory Academy’s elementary students, each grade level has an intervention teacher and an instructional aide alongside its three primary teachers. The intervention teacher’s role is integrated into the school day to allow students who need extra help to brush up on their foundational reading and math skills. Sometimes that means students are pulled out individually and other times for a small group session to work on targeted skills. It requires collaboration between teachers and the interventionists, said Clemmons, to plan out lessons targeted at sharpening students’ weaker areas.

“The intervention teacher will look at the target skills that we feel those students need to work on,” Clemmons said. “It could be the most gifted kid. It could be the one who’s really struggling because they’ve been absent.”

At the middle school level, students have a period focused on intervention. Some days they work on English and others on math.

The school also relies on its own assessments scattered throughout the school year. Those assessments guide the teachers’ approaches to learning and in building extra help a student may need, whether that’s extra support during class or additional support through after-school and Saturday programming.

However, as schools nationwide deal with a shortage in teachers, so is Wilder’s Preparatory Academy. The school has 11 substitute teachers across 79 faculty and staff members. That instability has also required extra preparation for grade-level leads like Clemmons to ensure that students are still able to access the learning they need.

Wilder’s Preparatory Academy’s performance levels have remained fairly consistent, despite the setbacks of online learning during the pandemic, according to test data. As a charter without labor unions, the school was able to provide more live instruction than nearby public schools and provided some in-person learning the summer before classes returned in person.

Still, Wilder’s Preparatory Academy is navigating similar issues involving absenteeism and socio-emotional well-being in the pandemic’s wake. The school has expanded its counseling staff to a six-person team to provide students with support.

“You’ve got to teach kids what they may not have received at home about self-confidence and being the best,” Wilder said. “Seeing people that look like you, that are doing some great things and teaching a sense of pride, all of that goes with the curriculum. Those are the extra pieces that are put in place to make kids excel.”

Daniel J. Willis, EdSource data journalist contributed to this story.

-

The hundreds of thousands of students across 23 campuses won't have classes.

-

Over 100 students from Cal Poly Pomona and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo learned life-changing lessons (and maybe even burnished their career prospects).

-

The lawsuit was announced Monday by State Attorney General Rob Bonta.

-

Say goodbye to the old FAFSA and hello to what we all hope is a simpler, friendlier version.

-

The union that represents school support staff in Los Angeles Unified School District has reached a tentative agreement with district leadership to increase wages by 30% and provide health care to more members.

-

Pressed by the state legislature, the California State University system is making it easier for students who want to transfer in from community colleges.