Everybody Loves The Sunshine: Black Angelenos Helped Shape The City — Don't Erase Us

A Black LA With 'Real Shape And Form'

When you're from Los Angeles and far from home, it is never unusual to spot a hint of the familiar in some on-screen backdrop: a car commercial, a music video, a glammed-up police procedural. But when you hail specifically from "Black Los Angeles" — finding your personal cross streets swirl up on television, especially from afar, prompts a unique set of emotions.

In late March 2019, I was time zones away from both those L.A.s, jammed into a hole-in-the-wall blues lounge in New Orleans. Waiting for change, I glanced at a soundless news report on the above-the-bar flatscreen. Something, though, held my vision. I couldn't look away.

Instantly, I recognized the corner of Crenshaw Boulevard and Slauson Avenue. I'd grown up just down the street. Five -- no -- three minutes away. Back then, I seldom saw my neighborhood on television, except, of course, if something tragic had transpired. Some crime blotter mishap: gang-related violence, a robbery. So when a jittery picture, framed from above, filled the screen. I already knew to steady myself. From the newsticker running across the bottom quarter of the screen, I deciphered that Nipsey Hussle, the L.A.-born and Crenshaw-bred rapper, activist and entrepreneur had been shot outside of his business, the Marathon Clothing store. In a short time, the newsticker reset to announce his death. Murdered. He was 33.

My heart broke into innumerable scattered fragments. The atmosphere shifted in the room, too. This mostly-Black crowd in a quickly gentrifying neighborhood, didn't just know who Nipsey Hussle was; they also deeply identified with what he symbolized. Pushback. Resilience. He could have moved "up and out"; he could have chosen to be anywhere, but instead he was taking his community back, taking into his arms. His example of re-investment offered a path toward hope.

Though I am a generation older than he was, this loss was my loss. This was the neighborhood that shaped me and, in certain ways, it is the place I'm always trying to get back to in my soul. He'd grown up in this same patch -- running the avenues and boulevards: Sweeping corridors lined with impossibly tall, listing palm trees, chockablock stretches of charming starter homes. He'd made a point to make these streets the backdrops of media photos and music videos. They, in turn, became his kingdom. And while many of those blocks still stood strong, unified in spirit, we all saw, in real-time, that the landmarks, the charm, the voices and rhythms of life there were in jeopardy. By choosing to remain in place -- visible -- he'd made inroads and impact.

This was not just the death of one man, but a dissolution of a dream. With each meeting he took, each check he wrote, each school he visited, each deal he brokered, Nipsey Hussle -- born Ermias Joeseph Asghedom -- was reframing Black L.A.'s narrative and ensuring who would be centered in it.

As his star power rose, he sunk his roots in even deeper. "I just want to give back in an effective way," he told The Los Angeles Times in 2018.

"I remember being young and really having the best intentions and not being met on my efforts. You're like, 'I'm going to really lock into my goals and my passion and my talents' but you see no industry support. You see no structures or infrastructure built and you get a little frustrated."

Nipsey saw the challenges up close: Underemployment, food deserts, struggling schools. "No structures. No infrastructures." He wanted a Black Los Angeles that had real shape and form. One that could support a generation's dream. He wanted a community that didn't exist just in the mind as a wish or a memory, but a location that had an address, a brick and mortar presence, a destination to navigate to, to cultivate, to pass down.

He knew precisely what was at stake as a Black Angeleno. He knew what it was like to be shunted aside, looked through, when not being relentlessly surveilled. He saw the dangers of displacement and invisibility. He knew that taking charge of one's own narrative began with self-assertion: "Self-made, meanin' I designed myself."

The Strength (And Power) In Numbers

Nipsey Hussle's story is just one tile of a vast mosaic. What does it mean to be Black in L.A.? Particularly at this moment? Much of it requires an emphatic self-naming and assertive space-claiming.

As a journalist, I keep my eye trained on statistics -- census numbers, pie charts, bar graphs -- that indicate shifts that we may not detect with a naked eye. Therein blooms stories. As a Black Angeleno those charts and calculations aren't abstractions. They are something you feel in your body, some sort of undertow in your day to day existence. Something has changed, power has shifted. Census numbers, like a Ouija planchette, pull attention toward power or possibility -- the vote, the money, the influence.

For many decades, Los Angeles had been known as a Black migrant "magnet." Folks came for the promise and the sunshine. The Black population in L.A. has dropped 30% since 1990, according to census data.

What happens when your population falls below a certain percentage? What's the magic number? 10%? Nine? Seven? Slip below this and you fade away into a ghost. When do you -- I -- any of us become transparent? Lost to vision -- of planners and the future.

I've been thinking more and more lately about this with COVID-19 stats and population comparisons flashing on all of my screens. The Black population of the city of Los Angeles clocks in at 8%. It reminds me of moments back in the newsroom. Once, I overheard a casual conversation about a roundtable being set up to chat with gubernatorial candidates. Not my beat, so not my headache. But still.

Reporters and editors were throwing in names. Community representatives from various pockets around the city. But after not too long, I realized that no one had mentioned anyone from the Black community -- even the most obvious names. I turned and asked if anyone was considering anyone from South L.A. or Leimert Park or Jefferson Park, West Adams, Watts-Willowbrook.

The response was quick, assured. "Well, we're looking at the numbers." I flashed on all the times decisions were made when I wasn't there, within earshot. Frankly, just because L.A.'s Black community had fallen below double digits didn't mean that they didn't have needs, goals, wishes. It shouldn't erase their place at the table. Blink and you go away.

Slights and cuts like this occur in a myriad of forms.The message sent, once again, was that unless you make some headline noise -- a tragedy, a cautionary tale, an insurrection, you're simply part of the backdrop.

It's been 30 years since the first grainy images of Black motorist Rodney G. King being brutally beaten by six LAPD officers made their way into our consciousness and onto our TV screens. This was yet another racial reckoning for Los Angeles -- as had been the 1965 uprisings in Watts, and, too, would be the civil unrest that lit Los Angeles on fire for three consecutive days in April 1992 in response to a jury's acquittal of those officers.

For a while, Black Angelenos -- their frustrations and their concerns -- were highly visible again. Roundtables were convened. Panels hosted. OpEd opportunities extended. But it was only a season. As the late poet, essayist and Angeleno, Wanda Coleman ruminated at yet another anniversary of both the upheaval and the unhealed wrongs:

"In understanding the dynamics that led to both riots, the value placed on the lives of African Americans and our history is central. Sadly, the powers that govern life in Los Angeles County have not given the matter full weight. Rather than right the social wrongs that plagued, and continue to plague, its Black constituency, the power brokers who run game in Southern California opted to eradicate the problem and decimate those communities, driving African Americans from the city."

In other words, this de-emphasis and erasure suggests something more deliberate and destructive, and, thus, contemptible.

Writing A Place Into The Narrative

We are nothing if not well-versed. Black Angelenos have known better than to simply wait. For someone else's solution. For someone to step aside or to make room. History shows us that best results came from workarounds, carving out one's place; not waiting for a seat at the table, but making one's own table.

As a child, one of the first stories I memorized about star architect Paul Revere Williams involved his dexterous sketching technique. As a Black man working with a largely white clientele, one of the tricks he'd taught himself was to draw upside down. He intuited that white clients may have wanted the brilliance (and status symbol) of his designs, but they might not want to sit next to him as he worked out his ideas based on their dreams. The idea was to focus on the design, not the man. It was an act of survival, a specific-to-him tool of the trade.

It made my blood boil, but the story was exceedingly instructional. He had a plan. I was -- and still am -- enthralled by Williams' buildings for their elegance and majesty. But, even more for his broad scope, his dexterity. Williams' buildings are the visual definition of why I love Los Angeles. The grand entryways, the sweeps of staircases that appear to arrive from nowhere, the sleek breezeways, the delicate play of L.A.'s quintessential powdery light, moving through living spaces.

Williams' built legacy is all around us: Single-family dwellings, civic and commercial buildings, public housing. He renovated structures and spaces in one of my most beloved (and now gone) structures in the city, the Ambassador Hotel. He was also part of the design team for the Los Angeles International Airport, which signaled to travellers that when they arrived in L.A. they'd landed in the future. But any Black Angeleno could roll out the many ways in which the city was stuck deep in its legacy of redlining.

Sometimes, if the mood hits, I take visitors on a long surface-street ride west to the Pacific Ocean, along Sunset Boulevard. When we close in on the Beverly Hills Hotel, I point out the sign with the elegant white script that welcomes guests to "Pink Palace'' -- and make note that the distinctive logo was written in Williams' hand. There is a spacious extended metaphor in his dexterity, in all the many ways he wrote himself into the landscape.

Cognitive Dissonance: Sunshine And Segregation

For years, Los Angeles was the dream destination for thousands of migrating Black Americans. The odds that you might settle on L.A. as an endpoint especially increased if you had people who had already paved the way. A room. A job lead. A new page to begin your new story. Writing in her expansive social history, "The Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America," historian Candacy Taylor explores the dissonance between dream and actuality for California-bound Black travellers. Of course, everyone loves the sunshine -- the "perfect climate" and images featuring the Pacifc Coast Highway hugging the Pacific sold L.A. better than any assemblage of adjectives could.

"Unfortunately, most black migrants looking for the American Dream in Los Angeles found the City of Angels even more segregated than the South. As one migrant from Baton Rouge, Louisiana observed, the division was so dramatic, depending on where one lived, entire populations were erased."

This was by design. Restrictive housing covenants that stipulated where people of different ethnicities, races, religions could live was a long-standing practice in the region. Los Angeles boosters in the early 1900s sold Los Angeles as the "White Spot," a term derived from maps produced by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. While it typically referred to L.A.'s relative prosperity and low unemployment, it had a racial cast to it. Later, slogans with double-edged meanings, employed by neighborhood councils and realtors, were far from sly "Keep the White Spot white."

That history lives with us. We coexist alongside remnants of it. Many decades of aggressive redlining have left neighborhoods that Black Angelenos have been cordoned off into and have, for generations, avoided sweeps of aggressive gentrification. They had, until very recently, been considered "undesirable" or "dangerous" or "run down." They were made both highly visible and invisible by this set of euphemisms. And that was fine. Because it made those spaces our own.

I used to forget just how under-the-radar we flew -- especially in the eyes of outsiders. When an East Coast writer friend, also Black, began visiting L.A. on the regular, back in the 90s, he found himself pulled into an orbit of film and TV meetings and the adjacent after-hours functions. I'll never forget his expression as he leaned over his lunch and whispered, deadpan: "I've been wanting to ask you for a while. Where are all the Black people at?"

It's funny, yet it's not.

For my generation, the toddlers and tweens who grew up amid the smoke and rubble of the Watts Rebellion, we are now wrestling with a recurring paradox. As children, we'd moved into these neighborhoods as ghosts under the cover of night. Our parents became blockbusters, moving us into homes and duplexes that old redlining laws were still trying to block and define. The "For Sale" sign remained in the lawn even after the sale. It wouldn't be removed until we were safely moved in. Fait accompli. We'd been trained at it. Not keeping small but knowing a way around the "rules." Dexterity.

-

- On Being Black In LA: Erasure Of The Black Community That Once Was

- Reparations And Reinvestment: Contemplating The Proverbial '40 Acres And A Mule' Today

- The 8 Percent: Exploring The Inextricable Ties Between L.A. And Its Black Residents

- Racism 101 on Take Two: How to Be an Ally, Code Switching for Survival, Deconstructing 'Defund the Police', Legacy of Slavery

- Why We've Shifted Our Approach To Telling Black Stories

We took these communities and made vivid lives in them. We took what was cast off and augmented its beauty. I watched my parents and their friends plant gardens that produced sustenance and a respite; convene community meetings; descend upon their local schools and demand for more. Almost immediately, "For Sale" signs went up on lawns surrounding our home near Slauson and Crenshaw. Even more shot up after Watts blew up in national news. These little Spanish stucco, red-tile roof homes were abandoned by white residents for the valley and beyond.

I think about this period of my own life as I hear anecdotes from Black Angelenos of my parents' generation who have held the line and refused to move. All of this is so delicate. Tenuous. One of my mother's longtime friends told me a story about one of her neighbors, another Black woman, who has been in her home for 50 years, maybe more. She'd watched her street, lined with skyscraper-tall palm trees, her own vast front lawn dotted with fruit trees turn -- "go over." White families vanished, scattered elsewhere along the arteries of freeways into the valleys and beyond. She listened as people described her pocket in coded language, as "inner city" or "urban."

"Well, you know that just means Black," she'd joke, but not.

In the last few years though, like so many other places that had been remade by waves of white flight, now, with a diminishing inventory of homes, streets like hers were aggressively sought out and highly visible. The migration loop was, she mused, like a boomerang. Her tract was identified as a Historic Preservation Overlay Zone, as a way to protect the feel and character. In a city that struggles with its past being razed, this level of insurance on one hand feels calming. But for those who live it it's a Catch-22.

My mother's friend tells me that her neighbor was feeling pressed. Some of the newcomers had made a point to make a "neighborly visit." But the reason for the house call was, first, to advise her how to landscape her home. Later, it concerned what colors to paint her trim. And finally, to inform her that her deck didn't pass muster. In order to correct it, she had to take out a second mortgage to pay for the major repairs. She was, at first, angered beyond words. The audacity. "There would have been no place for them to come to "protect" if we would have let it fall apart or had destroyed it. If we had fled too it wouldn't have the charm they're wanting so badly to protect," she confided. "Most likely it would all be gone." It too, a ghost. A dream turned into a memory.

* * *

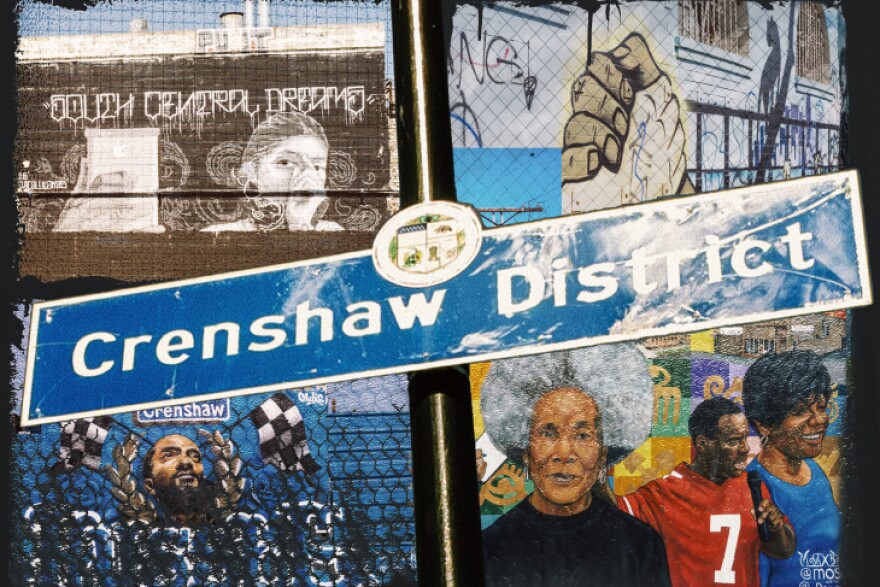

As I navigate the city, even in its sleepy COVID state, I grasp just how long the process takes. That "ghost state" doesn't occur immediately. It's a process. In the manner that a beam or patch of sun casts light on a fixed object: a shelved book's spine, a store sign, a painting. The fine details fade over time, the alteration, barely perceptible -- at first. As I move through another former stomping ground along the Vernon Avenue corridor, I'm reminded of a ride-along I had been assigned for a story about a photographer who was travelling the country documenting, "decaying urban environments" -- and consequently what remained. He told me that he was perplexed because he didn't understand why there were so many murals with Black faces affixed to walls in these South Los Angeles neighborhoods, some of which are now predominantly Mexican and Central American.

To him these bright tableaux seemed like detritus, not essential chapters to a complex history. "What do these murals have to do with the people who live here?"

I attempted to explain that for many decades these were among the few places Black people could live, and that these murals once adorned schools, and mini markets and storefront churches and auto body shops that had a predominately (but often not exclusively) Black clientele. It was a way to communicate, uplift but also impart history. Context. He seemed unmoved. His point was that because the Black people were no longer there, that the murals should vanish as well. "But wait," I could hear the imploring quality of my tone. I wanted to bring him around. But more, I wanted him to absorb. To recognize.

"These murals also tell a story of resilience. A message for all of us." He didn't budge. To him, these messages felt irrelevant. Years later, I continue to turn this story around, write my way through it. I can't wipe it free. Somehow it is indicative of what life often feels like here for me.

'Don't Sell Grandma's House'

This, I know, feels like a eulogy, but it is not. You have to disrupt the cycle, to discern a new way forward. Sometimes, out of the blue, I hear Wanda's voice. It slides in at moments as a soundtrack to old spaces I pass through. Wanda, our Cassandra, had been writing and reciting this lament, this warning, for years:

"When driving through the streets of Los Angeles, I too am gone -- beset by a painful sense of loss. The world I loved and lived in is vanished...It didn't have to be this way. Seeing the lives of its hopeful and vibrant community... smothered slowly under the kudzu of a persistent and prolific racism, West Coast style, as deadly as its empty promises of rebuilding and redress."

It's the stack of unkept promises that keep us in our emotions.

While COVID-19 has kept us away from each other, and out of our usual routines, the Los Angeles that we may re-emerge into -- after twin crises of a pandemic and economic fallout -- may be drastically unrecognizable. And what will Black Angelenos' already diminishing numbers look like?

A few days ago, a friend posted a link to a story that caught not just my eye, but my heart. It was a short feature about a Black-owned and run organization called Buy Back the Block L.A., which has begun holding weekly financial literacy workshops.

The group's founders were motivated not just by Nipsey Hussle's fame but his headstrong striver's hustle: to strengthen the foundations of these legacy-Black neighborhoods by teaching the community the importance of home ownership, building strong credit and cultivating a sustainable and secure economy for themselves. As they saw it, the dream did not have to die with the man. Quite simply, cofounder Danny Carter told the L.A. Standard Newspaper, "We felt that we needed to do something that kept his legacy alive."

Nipsey rose to neighborhood-hero status not simply because of his onstage swagger but for his commitment to being dexterous, thinking outside of convention, and, especially, for being present. He worked with neighborhood schools helping to support STEM programs and renovated basketball courts. He invested in the reopening of the old-school roller skating rink, World on Wheels, as a homebase for South Los Angeles kids of all backgrounds to socialize and showcase their strut. It was a way of repopulating the neighborhoods and recapturing a feel I remembered from my early days.

For Carter, it's building on what's already there -- a longevity and sense of place. Buy Back L.A. has adopted a blunt, to-the-point, slogan: "Don't sell grandma's house." Carter said, "[You] would be out of your mind...if you planned to sell...to someone who is not from our community. It's just that serious right now."

I'm always courting loss when I return "home." It is that serious. So truth told, it took me many weeks after Nipsey's death, to make my way deep into the unfamiliar familiar. In those early days, I didn't think I was up to that lap. The depth of loss felt cavernous. I worried about what it would mean that Nipsey was now yet another figure we spoke about in past tense. A ghost.

Through a raw twist of emotions, I began to count the many places Nipsey's image has bloomed, in murals, across the neighborhood, on Brynhurst, on Crenshaw, on Slauson. His image -- its symbol -- is as stubborn as kudzu. I have made a pact with myself to capture as many of these vivid tributes as I can. In this way they seem less like memorials, but declarations. Black people and their contributions feel less like ghosts and rather an infusion of spirit: A reminder that we are always picking up where someone left off. The work for Black Angelenos is always there to carry forward, because, like Nipsey knew, it is a marathon.

-

Lynell George is an award-winning Los Angeles-based journalist and essayist. A former staff writer for both The Los Angeles Times and L.A. Weekly, she focused on social issues, human behavior as well as visual arts, music and literature. She is the author of "No Crystal Stair: African Americans in the City of Angels" and "After/Image: Los Angeles Outside the Frame," a collection of her essays and photographs. Her latest book, "A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia E. Butler" was published in 2020.

-

My good friend used advance parole to leave the country and return. Now it's my turn to go back "home."

-

When you grow up in Anaheim close enough to watch Disneyland fireworks every night while your family can’t afford to go, you can’t help but feel like you’re on the outside looking in.

-

She sat down with us in April, nearly 50 years after the night she turned down Marlon Brando's Best Actor Oscar — which is still among the most memorable and contentious in Academy Awards history.

-

Latin America is no stranger to racism and colorism — just turn on a telenovela and see for yourself. And it’s alive and well in our own communities here in the U.S.

-

When you grow up identifying as "half white and half Mexican," the task of choosing what box to check on a government form isn't easy.

-

Growing up as the son of a Filipino immigrant dad and Russian American mom, Mark Moya felt equally attached to both cultures. He still does. Lately, he's been thinking more about their immigrant legacy and how it shaped him, especially after losing his dad earlier this year to COVID-19.