How West Hollywood Became LA’s Fabled And Flawed LGBTQ+ Haven

West Hollywood as a nucleus for LGBTQ+ culture in Southern California is practically set in stone.

The buzzing nightclubs filled with thumpy house music, packed bars and other flashy WeHo attractions have drawn thousands of people over the years, to visit and live. It's impossible to overstate its effect on the culture.

But the city wasn’t always full of rainbows. Let's see how it transformed over the years.

Early drag shows

During the Prohibition era, speakeasies became a popular avenue for gay-coded entertainment.

During the “Pansy Craze” between the late 1920s and early 1930s, drag shows (before they had that name) were gaining underground popularity. Jimmy’s Backyard, one of Hollywood’s first openly gay bars that opened on New Year’s Eve in 1929, along with B.B.B.’s Cellar, were popular destinations for LGBTQ+ people and the Hollywood famous.

Rae Bourbon was one of their most well-known performers. The revues, as the shows were called, would feature Bourbon and others dressed in feminine clothing singing cabaret style with music. “Boys Will Be Girls” and “Don’t Call Me Madam” were two popular shows.

Bourbon may have been transgender, but it’s not entirely clear. In 1955, she traveled to Mexico for “sex change” surgery — making her the first person to have any type of gender reassignment surgery in the U.S., as the papers claimed. But there were theories that she didn’t get that surgery at all, according to Bourbon historian Randy Riddle. In 1999, Riddle made a public records request for the FBI’s files on Bourbon in which the agency wrote that she actually had surgery for cancer.

Either way, Bourbon did carry herself differently when she returned. She swapped the “y” in her name for an “e” (Rae) and advertised the big news, including in “Let Me Tell You About My Operation.” Her life is an example of the limitations in those days. Being a “female impersonator” — as drag was harmfully called back then — landed Bourbon in legal battles multiple times in Los Angeles and in other states.

Harassment during the Depression and beyond

It wasn’t just booze that could get you arrested during prohibition — gay spaces were also illegal.

The police were notorious for harassing LGBTQ+ people. In particular, the LAPD, which had jurisdiction in Hollywood, and over bars like the two Bourbon frequented, nestled along a block of Cosmo Street, in an alleyway next to Hollywood Boulevard.

The LAPD was just merciless in their raids of gay bars.

“The LAPD was just merciless in their raids of gay bars,” according to Lillian Faderman, LGBTQ historian and a co-author of the book “Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics and Lipstick Lesbians.”

When B.B.B’s Cellar and Jimmy’s Backyard were raided in October 1932, the events drew such scrutiny that Variety called it “a drive on the Nance and Lesbian amusement places in town.”

-

Queer LA is your space to get the most out of LGBTQ+ life in Greater Los Angeles. This long-term project helps you figure out things big and small with a focus on joy.

-

We chose "Queer LA" to demonstrate that this project includes everyone in LGBTQ+ communities. Find it here, on-air at LAist 89.3, social media and more.

LGBTQ+ people became scapegoats as the Depression got worse. Government officials began to view the popularity of “impersonator” (drag) revues — and by extension the visibly gay community — as part of what plunged the city into bad economic times, according to historical records.

If someone was convicted of “masquerading” (dressing in drag), they could be charged a fine or required to serve a 10-day jail stint in 1930. Three years later, and further into the Depression, that person would be sentenced to the maximum penalty of six months in jail.

But in the next neighborhood over, in unincorporated West Hollywood, the Sheriff’s Department had jurisdiction, not the LAPD. Which made a big difference, says Faderman.

“They were not so merciless,” Faderman said. “So, I think that was why West Hollywood became ‘the gay spot’ … it was an escape from the real viciousness of the LAPD.”

A budding subculture

Once people got wind that they wouldn’t have to be under the department’s thumb in West Hollywood, the community flourished. Lesbians and gay men flocked there to find connection, live more openly and be in the film industry.

During the silent film era, one of its highest paid actresses, Alla Nazimova, became a bisexual icon by turning a hotel into a sapphic hub.

“[Her] mansion on Crescent Heights came to be called the Garden of Allah, which was sort of a lesbian retreat in the early years of the movie industry,” Faderman said.

The Garden of Allah was known for its swinging parties, harboring the secrets of the rich and powerful who visited the hotel to let loose. Nazimova hosted women-only pool parties, where they could spend time together away from the prying eyes of the media and public.

As the years went on, so many gay-friendly places came on the scene that you could literally fill a book. Entrepreneur Bob Damron, who lived in L.A. in his younger years and owned several gay bars, created yearly address books (now known as gay guides) to catalog them all — including in West Hollywood. A generation of people found places for community, pleasure and political organizing.

The abundance meant men could go cruising to find romantic partners and bathhouses could be used as hookup spots. Women could dance together at dedicated clubs. Even bookstores and coffee shops got on board after the Depression.

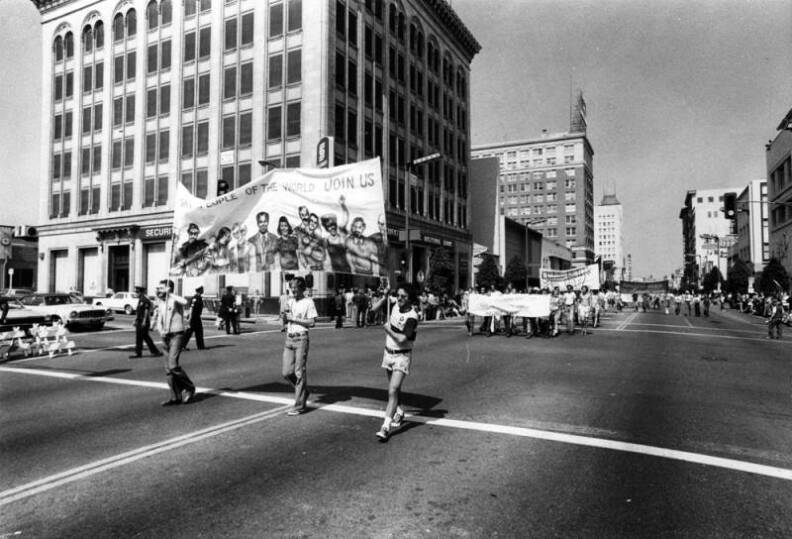

Back then, Hollywood and its neighbor to the west were both still important places for LGBTQ+ people to gather, despite the LAPD problems. When the first L.A. Pride happened in 1970, organized by church leaders and activists under the Christopher Street West Association, people didn’t march along the Sunset Strip — organizers picked Hollywood Boulevard.

Known then as Gay Pride Parade, marchers on June 28 walked in solidarity with simultaneous marches in other cities to mark the Stonewall Uprising of 1969. But L.A.’s parade was different. It was the world’s first legally permitted pride parade — a bit of paperwork that was hard-won. The LAPD chief didn’t hesitate to remind people that being gay was still illegal, and the police commission piled on extra permit costs to the point where the parade almost didn’t happen.

The commission thought the march would become violent, so they initially required bonds totaling $1.5 million and added minimum participant requirements — discriminatory practices that wound the commission up in court with the American Civil Liberties Union. The California Superior Court ordered the commission to issue the permit with just a $1,500 security payment. Thousands of people came out for the march.

The creation of ‘Boystown’

The feelings of security and community were great, but those weren’t shared by everyone. Somehow, being gay became conflated with being white and wealthy in West Hollywood. The nickname “Boystown” became synonymous with the area. There’s no one thing that led to this, but it got a reputation for exclusivity.

It could be because of the type of businesses that opened up. Ah Men, the first gay retail business in West Hollywood was designed for rich men. The upscale clothing spot, which opened around the early 1960s, largely defined popular gay men’s fashion, with see-through mesh outfits and tight shirts.

You couldn’t get in apparently unless you were good-looking and generally white, and usually looked like you were middle-class.

Studio One, a gay disco which opened in the 70s, was also a draw for wealthy white gay men to dance and meet. But for anyone else who didn’t fit that description, it wasn’t a welcoming place.

According to USC’s ONE Archives, owner Scott Forbes openly discriminated against gay men of color and women. Unless you were a wealthy white man, staff would find reasons to deny you entry, such as saying you had the wrong shoes on or that you didn’t smell right. Black and Brown men and women were required to show multiple forms of ID..

“You couldn’t get in apparently unless you were good-looking and generally white, and usually looked like you were middle-class,” Faderman said. “If you were a woman, I understand you had to produce five pieces of picture ID, which is ridiculous. So, women got the idea that they were not welcome.”

Around 1975, the Gay Community Mobilization Committee organized a boycott and protests against Studio One. Forbes agreed to stop the discriminatory practices but backtracked within weeks.

Some gay bars didn’t have these problems, but many places were stained by classism, racism and sexism. Even the lesbian bars back then seemed to be separated by class. At the upscale Club Laurel, Faderman recalls seeing two women come in with floor-length mink coats.

“I remember meeting a woman who told me she was an airline stewardess,” Faderman said. “And it wasn't until I knew her pretty well that I discovered that she was a teacher. She didn’t tell anyone at the Club Laurel that she was a teacher because she thought that was really scary.”

One of L.A. County’s LGBTQ+ famous spots, Jewel’s Catch One, was founded by Jewel Thais-Williams for this very reason. As a Black woman, she purposefully opened a gay Black disco club in Arlington Heights — away from West Hollywood because of discrimination.

The West Hollywood of now

West Hollywood has changed since then. There are some who are happy with the status quo — those who go to bars with hyper masculine go-go dancers. But there’s a growing number of people who have called out issues of exclusion.

The problem has even shown up in research. Between 2005 and 2006, university and Global Forum on MSM and HIV researchers talked to 35 men in L.A County to explore how gay men of color construct identity. George Ayala, currently the deputy director of the Alameda County Public Health Department, was a co-investigator for the study, published in 2017.

“They were basically saying out loud to us, there is such a thing as being a Black gay man. Not just a Black man. Not just a gay man, but a Black gay man,” Ayala said.

But the sense of disillusionment in West Hollywood was particularly strong. Many of those interviewed felt that being a man of color and gay wasn’t welcomed in the city.

Now of course people have found belonging there, but it boils down to who feels that most and why.

I think that WeHo has become more of a tourist attraction for cishet people to kind of ogle at us...

The solution for some has been to find community elsewhere. Mauro Cuchi, a drag king in L.A., says that drag culture tends to be better in other areas.

“I think that WeHo has become more of a tourist attraction for cishet people to kind of ogle at us as a queer community, as entertainment,” Cuchi said. “They've really commodified it.”

Cuchi has performed at places like Redline Bar in downtown L.A. The scene, they say, is becoming very artistic and conceptual. One of the shows Cuchi’s watched has a scene with a cake and a picnic table where the queen puts cake all over her body.

“These are really fun, really amazing moments that are outside of WeHo,” they said. “And that are also, in my opinion, more welcoming to a lot of us.”

Picturing the future

If West Hollywood was founded today, Faderman believes we wouldn’t have the same problems.

“There’s so much more awareness of inclusivity today than there was in the 1970s and 1980s,” she said. “If a place tried to have the policies that Studio One had, for instance, there’d be a lot of protest in the LGBTQ community.”

Inclusivity has increasingly become a focus as people try to make the city better. So in another few decades, West Hollywood could be very different.

More clubs are opening that center around inclusion, like Stache, which bills itself as a place “for every form of self-expression.” The City Council updated its Pride crosswalks with more inclusive colors. And mayor Sepi Shyne is the first woman of color elected in the position.

As history shows, these kinds of changes can have an impact on how people experience West Hollywood. And under Shyne, she’s been vocal about the city’s responsibility to be a safe place for everyone.

“Yes, that does mean lesbians, transgender folks, transgender men and women, and nonbinary and gender expansive folks,” Shyne said.

-

Restored with care, the 120-year-old movie theater is now ready for its closeup.

-

Councilmember Traci Park, who introduced the motion, said if the council failed to act on Friday, the home could be lost as early as the afternoon.

-

Hurricane Hilary is poised to dump several inches of rain on L.A. this weekend. It could also go down in history as the first tropical storm to make landfall here since 1939.

-

Shop owners got 30-day notices to vacate this week but said the new owners reached out to extend that another 30 days. This comes after its weekly swap meet permanently shut down earlier this month.

-

A local history about the extraordinary lives of a generation of female daredevils.

-

LAist's new podcast LA Made: Blood Sweat & Rockets explores the history of Pasadena's Jet Propulsion Lab, co-founder Jack Parsons' interest in the occult and the creepy local lore of Devil's Gate Dam.