How One Woman Navigated The Grief Of Suicide — And What She Hopes It Can Teach Others

There's no official playbook for how to navigate the grief of a loved one taking their own life. It's a journey that Charlotte Maya knows all too well.

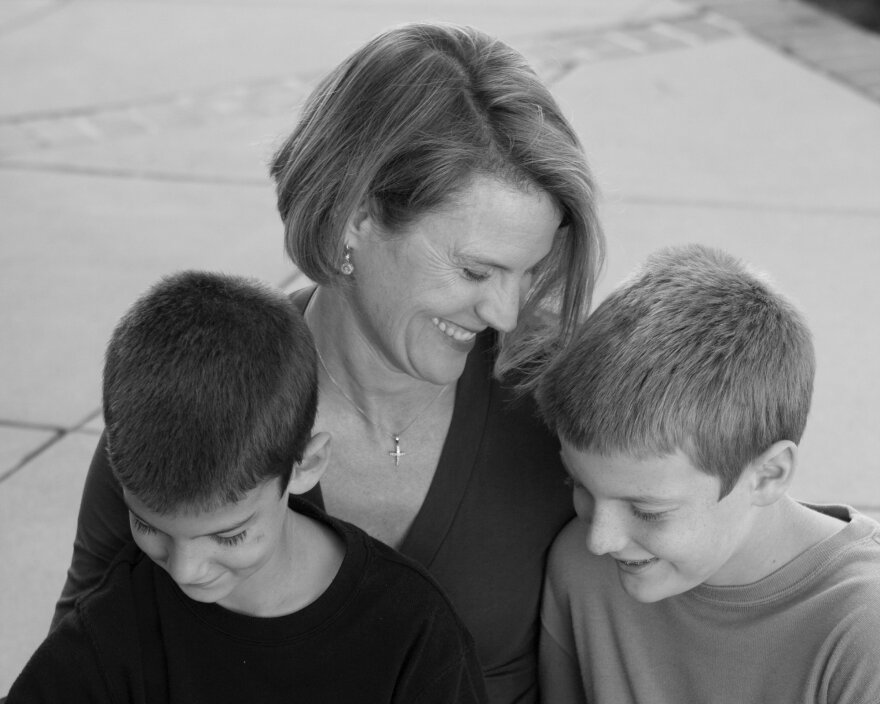

In 2007, Maya came home from a hike with her two sons and family dog to find police and a priest in the driveway of her Southern California home. Her husband, Sam, who said he was staying behind to take a nap, had instead killed himself.

His suicide came totally out of the blue to Maya and catapulted her and her sons into the unchartered waters of grief and loss.

This past year, Maya published Sushi Tuesdays: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Resilience. The memoir details her family's experience navigating the aftermath of her husband's death and the stigma of shame that often accompanies a suicide.

"Suicide was a story demanding to be told," Maya told our newsroom's AirTalk program, which airs on LAist 89.3 FM.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide is among the top 10 causes of death in the United States, with an estimated one death every 11 minutes.

Maya and others directly affected by suicide know that talking about it makes a difference. It took her more than a decade to write the book, primarily out of fear that she would be ostracized. What Maya discovered was the opposite.

"People are aching to have this conversation," she said.

Why fluency around suicide is so important

When the police showed up at her house in the immediate aftermath of her husband's death, they told Maya they would help inform her two sons that her husband had died, but she had to tell them how. Maya's kids were 6 and 8 years old at the time, and while telling them was the "hardest thing I've ever done," she also found that this truth would connect her to so many others.

-

At magnitude 7.2, buildings collapsed

-

Now spinning in front of Santa Monica apartments

-

Advocates seek end to new LAUSD location policy

The signs of suicide — which include depression and other mental health concerns — might not always be obvious. That was Maya's experience. Now that she has a deeper understanding of suicide, there are things she can look back and see as signs. This "fluency around suicide," she said, is something we should all have.

One of the signs in the Maya's husband case was weight loss. Sam had only lost five or six pounds in the months prior to his death, but looking back, Maya now knows that weight loss can be a sign of stress and something to look for in a loved one.

The night before Sam's suicide, he had the family's will and trust out on the counter. But Maya was a will and trust attorney. It wasn't extraordinary to have these materials out around the house.

"What if I had asked him?" Maya now wonders.

What if she had known what signs to look for? What if we all knew what signs to look for?

Signs of suicide

The National Institute of Mental Health says the following could be warnings signs of suicide:

How to navigate the aftermath

In the wake of Sam's death, Maya was left not only trying to make sense of an immeasurable tragedy, but having to pick up all the pieces of the family that were once shared with her husband. The kids had to get to school on time, bills had to be paid, and she also knew she needed to make time for herself to process the loss.

"The guilt is crushing," Maya said.

Like many others who experience the loss of a loved one to suicide, it's natural to wonder what was missed. Maya knows things now that she didn't then. At the same time, she reminds herself and others: "I couldn't know what he wasn't saying out loud."

Processing guilt was part of grieving.

Lean on friends

As Maya worked on family finances, scheduling carpools and figuring out passwords to shared accounts, her community of friends and family stood by her every step of the way.

She calls the friends that came through in ways big and small the "Janes."

Some could offer meals, others could offer rides, but everyone had something to give. "People showed up in unbelievable ways."

One example: A friend noticed she was always running late for school so she started showing up at her home with time to make sure the boys were on time. Maya dubbed this friend "engineer Jane."

"One of the things I really wanted to convey in this book, people always ask, 'What can I do to help?' Maya said. "I always say is if you have a gift — and you do, everybody has a gift, everybody has their own sort of quality of light that they shine in the world — then whoever you want to help needs that gift."

Engineer Jane told her: "Charlotte, I can't cook and I don't have any social skills, but I have noticed that you are always late to school."

Maya said that friend showed up at her doorstep for months.

"I was on time when she was in charge and I didn't need 12 engineers on my doorstep at 7:45. I just needed one."

Take up an activity

For Maya that was running. She joined a group of running friends at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena.

"Running turned out to be a really effective way to pound out a lot of angry feelings, because I was heartbroken," she said. "But I was also mad and I was, I was sad, but I was so confused."

Maya said being part of a running group was not only community, but "also a very bodily way to experience the grief and to move through the grief."

Protect time for your own grief

Maya also made a point of showing up for herself. She had therapy on Tuesdays, which was also the day of her favorite yoga class. Soon, Tuesdays became "a sacred day for self care." She called it "Charlotte Shabbat."

From week to week, when Tuesdays came around Maya would drop everything and do whatever she felt she needed from the time she dropped her sons at school until she had to pick them up.

Sometimes that meant taking a yoga class, other times that meant tapping into her deep sadness and grief. And often times, that meant taking herself out to lunch for sushi — the inspiration for her memoir's title.

Listen to the full conversation

Resources

-

- Steinberg Institute website, links to mental health resources and care throughout California

-

- Institute on Aging's 24/7 Friendship Line (especially for people who have disabilities or are over 60), 1-800-971-0016 or call 415-750-4138 to volunteer.

-

- Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, 24/7 Access Line 1-800-854-7771.

-

- The Crisis Text Line, Text "HOME" (741-741) to reach a trained crisis counselor.

-

- California Psychological Association Find a Psychologist Locator

-

- Psychology Today guide to therapist

-

If You Need Immediate Help

-

- If you or someone you know is in crisis and need immediate help, call the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or go here for online chat.

-

More Guidance

-

- Find 5 Action Steps for helping someone who may be suicidal, from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

-

- Six questions to ask to help assess the severity of someone's suicide risk, from the Columbia Lighthouse Project.

-

- To prevent a future crisis, here's how to help someone make a safety plan.

-

Fentanyl and other drugs fuel record deaths among people experiencing homelessness in L.A. County. From 2019 to 2021, deaths jumped 70% to more than 2,200 in a single year.

-

Prosecutors say Stephan Gevorkian's patients include people with cancer. He faces five felony counts of practicing medicine without a certification.

-

April Valentine died at Centinela Hospital. Her daughter was born by emergency C-section. She'd gone into the pregnancy with a plan, knowing Black mothers like herself were at higher risk.

-

Before navigating domestic life in the United States, AAPI immigrants often navigated difficult lives in their motherlands, dealing with everything from poverty to war.

-

There are plenty of factors in life that contribute to happiness. But could keeping in touch with your loved ones be the most important?

-

The new California law makes it a crime to sell flavored tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes.