Why The Biltmore Hotel, 100 Years Old This Year, Plays A Big Role In Oscars History

The Biltmore has long been sprinkled with stardust.

In a rather ordinary, unobtrusive hallway at the legendary Millennium Biltmore Hotel in Downtown Los Angeles are photos from its century-long history. Liveried employees, movie stars, and socialites (including the fascinating Peggy Hamilton, “the Biltmore girl”) and L.A.'s most famous murder victim line the walls faded with glamour and mystery. But one sticks out.

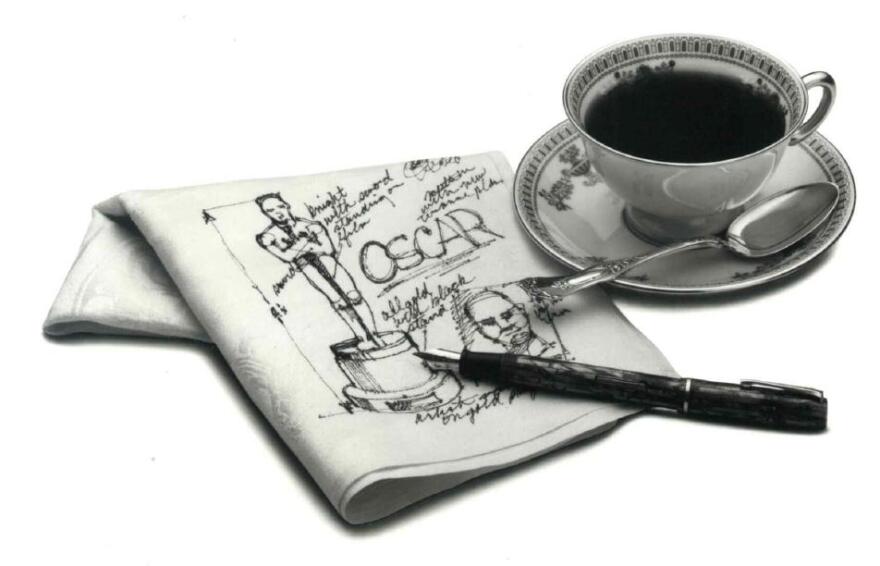

It is a photo of a recreation of a napkin — featuring a sketch of what we now know as the Oscar.

On May 11, 1927, the newly formed Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences held its first banquet at what was, at the time, considered L.A.'s most lush hotel.

On this day in 1927, the Academy was founded during a banquet at LA’s Biltmore Hotel. And the rest is history. pic.twitter.com/u1E3f8UHuf

— The Academy (@TheAcademy) May 11, 2018

Movie star Douglas Fairbanks was elected the Academy's President, as more than 300 industry pioneers looked on. As members discussed plans, MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer floated the idea of a potential awards program for excellence in motion pictures. That’s when Cedric Gibbons, MGM’s legendary art director, allegedly took out a pen and deftly sketched a statue of a stylized knight holding a sword, standing resolutely atop a film reel.

And thus, the iconic Academy Award was born

Or was it? “Nobody's actually seen the famous napkin, but it's definitely added to the sort of allure of the Biltmore Hotel,” says Alex Inshishian, program manager at Los Angeles Conservancy.

Since it opened in 1923, the Biltmore has been filled with titillating tales, momentous historical events, and of course ghosts — including a little boy on the third floor who tells employees, “Don’t follow me, this is where I live.”

In 1960, the Democratic Party Convention was held at the hotel, with nominee John F. Kennedy receiving a hero’s welcome.

“Then, of course, it became famous for the Presidential Suite. FDR stayed there, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan. I believe Bill Clinton also stayed there,” Inshishian says.

In 1964, the Beatles landed on the roof in a helicopter before taking over the Presidential Suite. And then there are the countless movies filmed in its large hallways and grand ballrooms — everything from Chinatown to Ghostbusters and Wedding Crashers.

The Biltmore also has its place in civil rights history. According to Inshishian, it was listed in the last two editions of The Green Book as a safe place for Black travelers to stay, and also served as an important landmark in the fight for LGBTQ rights.

So many stories spread out over a century of momentous growth and change in the City of Angels.

The host of the coast

In 1921, plans began for the grandest hotel Los Angeles had ever seen. Spearheaded by hotelier John McEntee Bowman, a site was chosen in the heart of bustling downtown Los Angeles across the street from Pershing Square, then a lush tree-lined park.

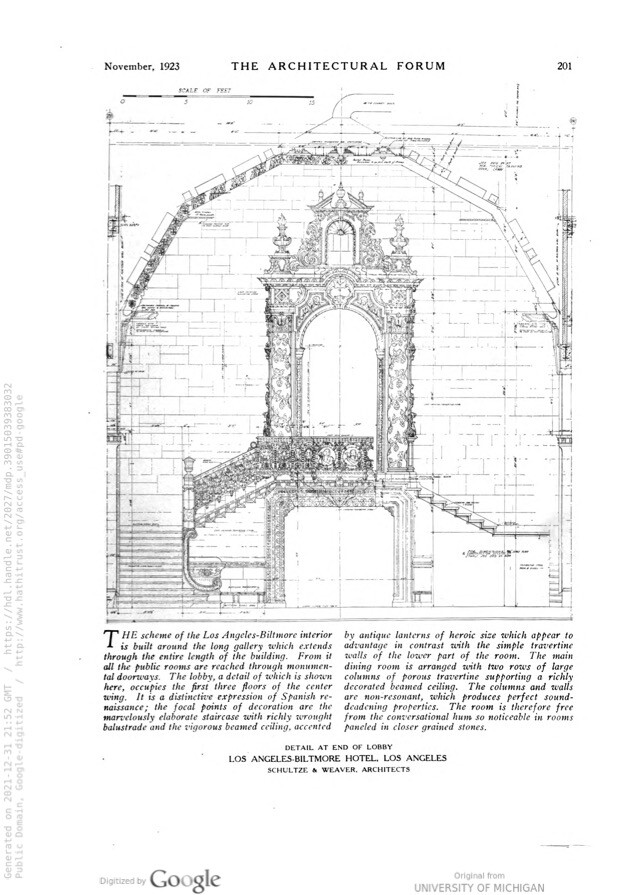

In a major get for the rugged, upstart city, the Biltmore was designed by the firm of Schultze and Weaver, who also created New York’s legendary Waldorf Astoria. “The architecture itself is a Beaux-Arts style… It's essentially an Italian sort of Romanesque style,” Inshishian says.

“It really is designed to project this sort of European upscale feel — the idea that you might be going into one of these Grecian temples or Roman temples, and so you have materials that are supposed to replicate marble or are marble, travertine, those sorts of things… there are murals of Greek gods on the ceilings, some by Giovanni Smeraldi, who also helped work on the blue room over at the White House. It is a very ornate style, and it’s supposed to give off this sense of affluence for people that are coming through.”

On Oct. 1, 1923, the doors of the Biltmore were thrown open to a clamoring public. The next night a mammoth gala for 3,000 was held, while thousands more were turned away. Tinseltown luminaries like Mary Pickford, Jack Warner, Cecil B. DeMille, and Myrna Loy dined in eight different dining rooms, serenaded by six orchestras. The Los Angeles Times reported that the gala was one of the most “remarkable occasions in the social life of the city,” where “society matrons, debutantes, celebrities from the film world…moved among banks of flowers, palms and formal floral pieces set about the great corridors and salons.” The Times further reported:

“Amid scenes that, for the sparklingly splendor and merriment, must have rivaled the illustrious settings when the princess was married to the prince in all the glory of the storied castles of Old, Los Angeles took the new Biltmore Hotel to her bosom last night. And from the auspicious wonder of ceremony and the spirit of it all, it looks as though the two are to “live happily together ever afterward.”

The Biltmore immediately became an important center of commerce, business, and society during the boom time of the 1920s. “Before the Biltmore, the main hotel was the Alexandria. And once the Biltmore came in, it kind of took over the reins of being the place to be, the hotel to stay at,” Inshishian says. “If you were a who's who, or if you wanted to see a celebrity, you were going to the Biltmore. So much so that they had to hire bouncers in the '20s and '30s because there were a lot of just lookie-loos that wanted to see all the big Clark Gables and all these people that were kind of hanging out at the hotel.”

The secret speakeasy

There was one problem. A pesky little thing called Prohibition. The Biltmore Hotel opened smack dab in the middle of America’s great failed experiment, which meant alcohol could not legally be served in its glittering ballrooms and eateries.

And so, according to the hotel’s current general manager, Alex DeCarvalho, a ruse was devised. In the great Gold Ballroom (currently being meticulously restored), a low-molded panel in the back corner leads to the Biltmore’s long-forgotten speakeasy.

“Back then, there would've been a bouncer over here. And you had to have a secret password and everything. Then you open this door,” he says. The door swings open to reveal a set of rickety stairs, which leads to a tight, narrow room where celebrities like Gloria Swanson once drank at the forbidden bar.

On the opposite side of the cluttered space, which now feels more like a utility closet than a madcap jazz-age speakeasy, is an exit where patrons could be quickly shuttled out if the LAPD happened to arrive. Of course, knowing the LAPD in the 1920s, they were probably just stopping by for a drink.

Oscar-mania

In 1928, the Biltmore Hotel was expanded. Known as the Biltmore Bowl, this massive ballroom, said to be the "largest hotel ballroom in the world," designed to hold over 2,000 people, soon became the hottest ticket in town (due to unfortunate renovations, it is now split into two rooms, its ceilings dramatically lowered). “The Biltmore Bowl really became a huge nightclub in the 1930s,” Inshishian says.

On Nov. 10, 1931, the Academy Awards were held at the Biltmore Bowl for the first time. According to Variety, 2,000 seated guests (and 500 more without seats) sat through the ceremony, which ran from 8 p.m. to 1 a.m. The Hollywood Reporter called it the “greatest event in Academy history,” reporting:

“Despite the great amount of confusion encountered by those seeking admission to the banquet room and much disturbance in finding proper places at tables, the affair was the most brilliant ever known in the picture industry. The streets outside the Biltmore and the lobbies of the hotel were congested with thousands of people, trying to get a glimpse of their favorite actor or actress.”

The big winners that night were Best Actor winner Lionel Barrymore and Best Actress Marie Dressler. “There was a little stir and some chuckles in the audience,” The Hollywood Reporter wrote, “when [child star] Jackie Cooper, seated at the speaker's table… had found the proceedings too much for him and was slumbering peacefully with his head on Marie Dressler’s shoulder.”

Cooper wasn’t the only one feeling bored. Unlike the effusive Hollywood Reporter, its rival trade Variety ripped the interminable evening to shreds, reporting:

“A long-winded, verbose, political and dull evening of a nature which will repel many a Hollywoodian next year (unless memories dim and time makes ‘em forget) it certainly was vested with considerable official color.”

All in all, eight Academy Awards ceremonies i were held at the Biltmore Bowl — in 1931, 1935 to 1939, 1941 and 1942. The ceremony became a powerful marketing tool for the Biltmore Hotel and a point of pride.

The Black Dahlia connection

On Jan. 9, 1947, at around 6 p.m., a striking pale woman entered the Olive Street lobby (now the Rendezvous Court) of the Biltmore Hotel. Her name was Elizabeth Short, known to history as the tragic Black Dahlia.

The Biltmore Hotel has long been rumored (a rumor encouraged by the LAPD) to be the last place Short was seen alive before her brutalized body was discovered in an empty lot on Jan. 15, 1947. Although author Steve Hodel, author of Black Dahlia Avenger, argues that Short was in fact seen later in the week leading up to her murder, her time spent at the Biltmore offers a tantalizing glimpse into her frame of mind.

When Short entered the lobby, she appeared to be looking for someone, and her nervous, fidgety demeanor attracted attention. “She looked more like Northern California — well dressed, buttoned up, edgy, her fingers twitching nervously inside her snow-white gloves,” Hodel writes. “Increasingly people in the lobby couldn’t keep their eyes off her, this woman in the black collarless suit accented by a white fluffy blouse that seemed to caress her long, pale white neck.”

Short made numerous calls during her stay at the Biltmore, drank Cokes at the bar, and paced nervously, clearly waiting for someone. Finally, at around 10 p.m., it appeared her latest call was successful. She then purposefully strode out of the lobby, newly invigorated. Hodel writes:

“She turned back one last time toward the hotel, noticed her reflection in the glass door, and straightened the large flower that shone like a white diamond pinned atop her thick black swept-back hair. She paused briefly to straighten it, smiled at the onlookers who stared at her from inside the glass divide, and then turned south, walking toward 6th Street into the deepening fog that curled around her like smoke, making it seem as if she were disappearing into the night. The darkness had a life of its own, folding her into itself.”

Unsurprisingly, Short’s ghost is said to haunt the Biltmore to this day, particularly on the 10th floor.

“She never smiles or acknowledges anyone; she seems to be frightened and looking for someone,” Janice Oberding writes in The Big Book of California Ghost Stories.

“There is also the story of a man who rode the elevator with a beautiful dark-haired woman…neither said a word…she got off first and was gone before he realized what direction she went. It was only later when he saw a photo of her that he realized he’d shared the elevator with the Black Dahlia ghost.”

A magical ascension

The Biltmore is also the site of a mystical mystery. Paramahansa Yogananda was the author of the influential Autobiography Of A Yogi, founder of the Self-Realization Fellowship and credited for being the “father of yoga in the west.” On March 7, 1952, he came to the Biltmore to give a speech at a dinner held in the honor of India’s ambassador to America, Binay Ranjan Sen.

After giving a speech extolling world unity and peace to 250 people in one of Biltmore’s ballrooms, Yogananda slid to the floor and died. Believers think that the guru willingly made a conscious exit from the body, entering what is known as mahasamadhi. According to followers, in the days leading up to his death, Yogananda had hinted at his upcoming exit.

“My body shall pass but my work shall go on. And my spirit shall live on,” he told them. “Even when I am taken away, I shall work with you all for the deliverance of the world with the message of God.” According to one devotee, hours before his death, he said:

“Do you realize that it is just a matter of hours, and I will be gone from this earth?”

Though the official cause of death was a heart attack, the legend surrounding Yogananda’s death soon deepened. His body was taken to Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale. According to the Los Angeles Times:

“Before the funeral, however, Forest Lawn manager Harry T. Rowe raised eyebrows by issuing a notarized letter to the fellowship that asserted that Yogananda’s body had not begun decomposing, even 20 days after his death…. “This state of perfect preservation of a body is, so far as we know from mortuary annals, an unparalleled one. . . . Yogananda’s body was apparently in a phenomenal state of immutability,” wrote Rowe, apparently at the request of the fellowship. “No odor of decay emanated from his body at any time.”

With stories like these, who knows what the next 100 years will bring?

-

Restored with care, the 120-year-old movie theater is now ready for its closeup.

-

Councilmember Traci Park, who introduced the motion, said if the council failed to act on Friday, the home could be lost as early as the afternoon.

-

Hurricane Hilary is poised to dump several inches of rain on L.A. this weekend. It could also go down in history as the first tropical storm to make landfall here since 1939.

-

Shop owners got 30-day notices to vacate this week but said the new owners reached out to extend that another 30 days. This comes after its weekly swap meet permanently shut down earlier this month.

-

A local history about the extraordinary lives of a generation of female daredevils.

-

LAist's new podcast LA Made: Blood Sweat & Rockets explores the history of Pasadena's Jet Propulsion Lab, co-founder Jack Parsons' interest in the occult and the creepy local lore of Devil's Gate Dam.