What Happens If LAUSD’s Enrollment Doesn’t Stop Dropping? 2 Schools Offer Painful Previews

Twenty years ago, Los Angeles Unified schools were badly overcrowded. More than 737,000 students attended district schools back then, enduring long bus rides or odd year-round schedules to relieve the capacity pressure.

Now, LAUSD faces the opposite problem. The district’s enrollment declined for two decades before lurching downward at the start of the pandemic as parents fled the uncertainties of distance learning and COVID-era restrictions on classrooms.

Today, just over 430,000 students attend LAUSD-run schools. California uses enrollment to set school funding levels — and operating half-empty campuses comes at a cost.

“We continue to spread our campuses so thin,” said Adaina Brown, a regional superintendent who oversees schools in LAUSD’s Local District West, "with staff that can barely get [students] English, math, science and history. They deserve so much more.”

This is the reasoning behind two recent district proposals — to close one LAUSD middle school and to relocate another — that offer a preview of the anguish that be could awaiting other LAUSD neighborhoods if present enrollment trends do not reverse.

‘Why Do They Keep Doing Us Like This?’

On Jan. 18, teachers at Pio Pico Middle School got word LAUSD officials were planning to close their Mid-City campus and hand it over to another fast-growing district program.

At the same time, teachers at Orville Wright Middle School in Westchester learned they’d soon be moving to a nearby high school complex, with Wright ceding its massive campus completely to a charter school.

District leaders say they haven’t officially decided whether to proceed with either move. Initially, LD West officials said the school board would vote on the Pio Pico and Wright proposals this week — but neither move was on this week’s agenda.

Still, neither proposal is officially dead — so parents, teachers and students at both schools have been pushing back loudly. Their concerns span just about every issue that makes school closures difficult, from charter school politics, to safety concerns, to the needs of students with disabilities.

To critics, the optics of the proposals are inescapable: faced with facilities conundrums, LAUSD is asking two groups of mostly low-income, mostly students of color to give up their spaces. Pio Pico is 90% Latino. Wright has one of the largest populations of Black students of any LAUSD secondary school.

“Our children are starting to feel like, ‘Why do they keep doing us like this?’” said Paris Brown, a Wright teacher who’s also Black. “That causes feelings of inferiority.”

But LD West leader Adaina Brown said the schools’ demographics underline exactly why something has to be done.

In 2002, during an era of busing and year-round calendars, Pio Pico’s campus once accommodated more than 2,200 elementary and middle school students; now there are around 350 students and only middle school grades.

Over the past 20 years, Wright’s enrollment has dropped from 1,500 to around 400 today.

Brown said that, with enrollment and school funding so closely tied, LAUSD struggles to afford anything more than basic programming at both Pio Pico and Wright.

“They deserve resources that we can staff their school with … more than just core content teachers,” said Brown. “They deserve a chance to say, You know what, this school takes me into college and career pathways we haven’t even thought of.”

“When we talk about children of color,” she added, “and what they deserve … These kids deserve a robust curriculum.”

The Case For Moving Wright Middle School

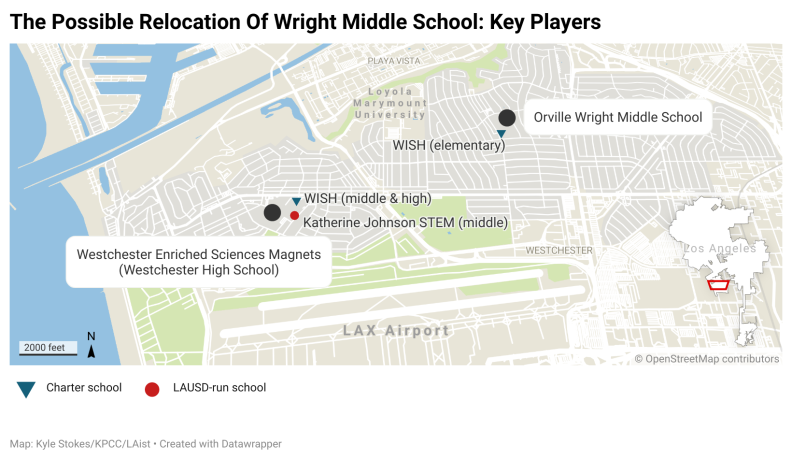

The Westchester neighborhood is no stranger to headaches over school facilities — and at least on paper, at least in theory, LAUSD officials can argue that moving Wright Middle School eases a number of those headaches.

First, there’s the former Westchester High School — now known as a collection of smaller programs known as the Westchester Enriched Sciences Magnets, or “WESM” for short.

Enrollment in WESM’s programs has also dropped sharply in recent years. District officials feel that moving Wright to WESM’s campus would encourage enrollment in both schools by creating a natural pathway between middle and high school grades. Brown said the two schools might even be able to share resources.

But parents at Wright say the district has provided few details about how this resource-sharing would work.

“You can’t just stick two schools together and assume it’s going to work magically,” said Dena Vatcher, president of the Wright Middle School PTO. “Their plan involves sticking schools at the same site with separate administration, separate staff, separate curricular focus, Here, make some magic.”

We just vested a whole new renovation and blood, sweat and tears into improving Wright.

Another consideration is WISH Charter School — a publicly-funded school run by an outside non-profit, not the school district.

WISH already operates an elementary program on half of the Wright campus under a state law that entitles charters to be housed at district-run sites; the “co-location” has been a hot-button issue in LAUSD politics for years.

If Wright students moved out, it would free up space on the campus for WISH’s middle and high school programs — currently housed at WESM — to move in. The charter’s executive director, Shawna Draxton, said that “in the absence of all context, it would be great to have all of our students on one campus.”

WISH’s educational model also makes the school a draw for students with disabilities. Draxton’s emailed statement included testimonials from parents whose children use wheelchairs — and who found it difficult to navigate the WESM campus. Wright’s campus would have fewer accessibility challenges.

However, Draxton also said WISH didn’t actively seek out this facilities swap, saying her students “are thriving on [the WESM] campus in many ways.”

“We empathize,” she wrote, “with the frustration that the Wright community members feel about the surprise announcement and the lack of an opportunity for the Westchester community to be part of the decision-making process.”

The announcement generated outcry for another reason: the district just completed long-planned renovations to add new lab spaces to Wright. If LAUSD’s proposal goes through, the district would hand the keys to Wright’s sparkling new facilities over to WISH.

Vatcher and other Wright parents are careful to avoid criticizing WISH, saying the central issue is that LAUSD hasn’t considered Wright’s needs — either to improve enrollment, or to make a potential move to WESM workable.

“If you want to talk about moving the school,” said Darryl Holmes, another Wright PTO officer, “first build what we had, and then let’s have the discussion … We just vested a whole new renovation and blood, sweat and tears into improving Wright.”

In an interview, Brown said that before moving Wright to the WESM campus, officials would first ensure that facilities on the high school site would be “upgraded and equitable … and definitely better, currently, before that move happens.”

Incoming LAUSD superintendent Alberto Carvalho starts his new job in L.A. next week, but nevertheless has already signaled his desire to delay the Wright move: “This issue will be thoroughly reviewed,” he tweeted, using a “Save Wright” hashtag.

‘Not When They’re This Young’

In many ways, Wright has long been a school without a neighborhood.

As a full magnet program, Wright doesn’t automatically enroll students who live in Westchester; even with the school under-enrolled, some parents report having to apply for admission. Meanwhile, three-quarters of current Wright students bus from other neighborhoods, especially Crenshaw, Baldwin Hills and areas of South L.A. along the 110 Freeway. This helps explain how more than 60% of the school’s students are Black in a neighborhood that’s 50% white.

The reason these students are willing to endure the long bus ride to a westside school, in part, is because of a feeling among parents that Westchester is a safer neighborhood — which further complicates parent feelings about a move to WESM.

“Several parents at these meetings,” said Vatcher — one of the relatively few Wright parents from Westchester — “are like, I don’t want my kids on a high school campus. Not when they’re this young.”

Meanwhile, parents say many Westchester residents bypass the two nearby middle schools — Wright and Katherine Johnson STEM Academy — to send their kids instead to LAUSD schools in Venice or Marina del Rey, or even across district lines to El Segundo Unified or Wiseburn Unified schools.

Those decisions are one reason why it’s difficult to dismiss LAUSD’s Wright proposal out-of-hand: if district officials want to draw those parents back into area schools, something has to change.

'We're Willing To Share'

Parents have had success pushing back against the district’s attempts to rearrange schools faced with declining enrollment.

Last fall, teachers in the Historic South Central neighborhood feared Trinity Street Elementary would be shuttered due to declining enrollment and handed over to Gabriella Charter Schools, which already shares the campus.

The union, United Teachers Los Angeles, launched a campaign against the move. This week, an LAUSD spokesperson confirmed Trinity would remain open to current students next school year.

But while operating schools below capacity comes at a cost, LAUSD currently has unprecedented budget surpluses — which raises a question about these new proposals: why now?

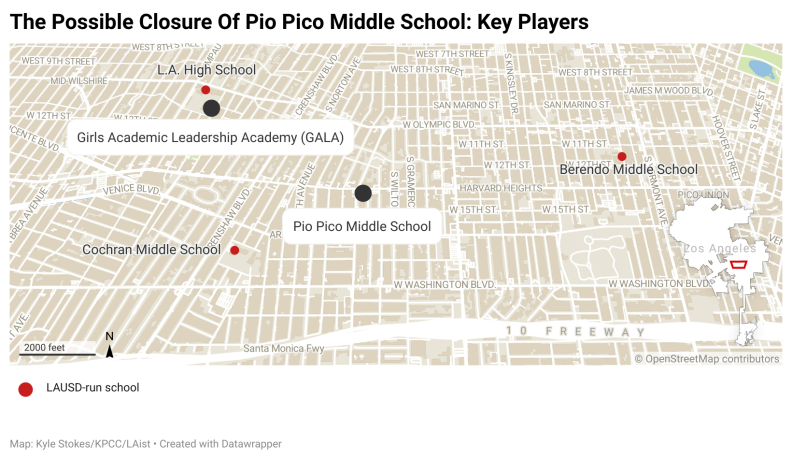

At Pio Pico, the answer is tied in with Girls Academic Leadership Academy, or “GALA” — a specialty LAUSD program that, at the time it opened in 2016, became the first non-charter single-gender school to open in California in more than 20 years. Currently, the school operates on a portion of the L.A. High campus.

A combined middle- and high school, GALA “became very popular, very fast,” said LAUSD’s Adaina Brown. “We knew they would eventually need their own campus or need their own space.”

Brown said LD West officials’ attention turned to a collection of three middle schools nearby; all three campuses were within two miles of each other, all of which had seen enrollment slip: Berendo, Johnnie L. Cochran and — the smallest of the three — Pio Pico.

By closing Pio Pico, LAUSD would not only free up space for GALA, but also bolster enrollment at two other nearby schools — and give former Pio Pico students access to more inventive, “outside-of-the-box” programming at Berendo or Cochran, Brown said.

But the district’s reasoning returns Pio Pico staff to the question: why now?

Pio Pico’s campus, which accommodated 2,200 students in the early 2000’s, currently enrolls around 350 students. The state law that permits single-gender schools currently limits GALA to 700 students. Even if that cap were lifted, couldn’t Pio Pico and GALA share the site? (GALA principal Liz Hicks deferred questions to her superiors at LD West.)

“We’re willing to share,” said Ofelia Quintero, a long-time special education teacher at Pio Pico. “Why are you pushing us out? There’s enough space for them to come in and leave us here.”

Fairness, In Facilities & More

Quintero notes that Pio Pico’s special education facilities have been retrofitted to serve students identified as having “intellectual disabilities.” That means the school has wider doors to allow wheelchairs and lift equipment, as well as special toilet facilities in certain classrooms.

Teachers wonder whether Berendo or Cochrane’s campuses have upgrades to serve these special education services. Pio Pico teachers said district officials have only replied with vague assurances so far.

In an interview, LAUSD LD West officials have said all students at Pio Pico who receive special education services would continue to receive those services at their new school. They emphasized that they wouldn’t commit to closing Pio Pico without addressing these concerns about special education facilities.

“We want to make sure that our special ed students receive, definitely, the facilities that they require before they move to Berendo and/or Cochran,” Brown said. “Those moves … could be simple upgrades or they may make some time. We want to make sure that happens before we put a timeline on anything.”

Sixth grader Matthew Avila has heard rumors of fights and gang activity at other nearby schools — and he wants no part of it. He hopes he can stay at Pio Pico.

“From what I’ve heard,” said Avila, “there’s a lot of really bad things happening at those schools, and I’m not too sure I really want to go there.”

His friend, Luis Chupina, agrees.

“It’s not really fair to us,” said Chupina, also a Pio Pico sixth grader. “There are so many sixth and seventh graders that have to go to a new school now.”

-

The hundreds of thousands of students across 23 campuses won't have classes.

-

Over 100 students from Cal Poly Pomona and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo learned life-changing lessons (and maybe even burnished their career prospects).

-

The lawsuit was announced Monday by State Attorney General Rob Bonta.

-

Say goodbye to the old FAFSA and hello to what we all hope is a simpler, friendlier version.

-

The union that represents school support staff in Los Angeles Unified School District has reached a tentative agreement with district leadership to increase wages by 30% and provide health care to more members.

-

Pressed by the state legislature, the California State University system is making it easier for students who want to transfer in from community colleges.