California's Groundbreaking Clean Fuel Laws Mean Big Changes For Polluting Trucks And Trains. Why It Matters

The California Air Resources Board, or CARB, the agency that regulates air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions in the state, unanimously passed two historic climate policies this week.

About new rules

- The "Locomotive Rule" sets rules to retire gas and diesel-powered freight and passenger trains by 2030 and sets timelines for transitioning those rails to low-emission technology. Most freight and passenger rails currently run on diesel, a major contributor to unhealthy smog and planet-heating emissions.

- The "Advanced Clean Fleets” rule bans sales of new gas and diesel big rig trucks by 2036 and requires fleets with more than 50 trucks to transition to electric or hydrogen-powered vehicles by 2042. It requires drayage trucks, the most polluting trucks, to be 100% carbon-free by 2035. It would also require garbage trucks and local buses to transition from fossil fuels by 2039.

Both rules have big implications for Southern California, which is home to the nation’s busiest ports and freight rail lines.

How we got here

The rules come after decades of advocacy by communities that live with some the dirtiest air in the country, in large part because of the freight rail and trucking industries at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports and in the Inland Empire.

The rules are the first of their kind — anywhere — and will likely have ripple effects. That’s what happened with California’s more stringent passenger car pollution standards: 17 other states adopted the law as well, pushing the car industry as a whole in the low-emissions direction. Both are expected to help significantly improve dangerous local air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades.

Why cleaner fuels have outsized health impacts

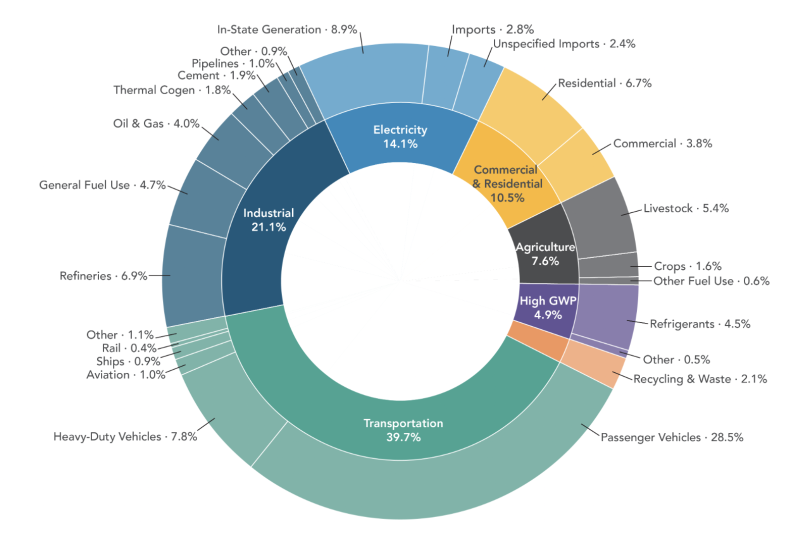

Medium and heavy-duty trucks make up only 6% of traffic on California highways, but they cough up about 35% of the pollutants that give Southern California its notorious smog and a quarter of pollutants from vehicles that get into the atmosphere and heat up the planet, according to the CARB.

The truck rule would target the most polluting trucks first: drayage trucks, which carry cargo to and from the ports of L.A. and Long Beach, as well as to and from warehouses booming in the Inland Empire. They’re now required to be 100% carbon-free by 2035.

Research has supported communities' experiences of how dangerous the pollutants from these trucks are, and how they exacerbate and trigger health issues including asthma and cancer, and even COVID-19. Low-income communities of color bear the biggest brunt of these impacts.

Gema Peña-Zaragoza, now 20 years old, grew up in San Bernardino, where big rig trucks and idling freight rail lines are a constant presence. Most people she knows have asthma or other health issues, including cancer.

“Everywhere you go in San Bernardino, there is heavy-duty truck and rail traffic,” Peña-Zaragoza said. “It is everywhere we go, and we cannot escape it. It will only continue to grow until my community is taken seriously and valued for our lives.”

She said the new policies are an essential step in the right direction, but there is still a ways to go to enforce the policy, as well as regulate smaller, but common fleets that have fewer than 50 trucks.

“We have allowed these industries to get away with so much for far too long, and we cannot have that any longer,” said Peña-Zaragoza. “We cannot accept any more crumb solutions or risk losing any more members of our community. My community members are given no choice but to live next to these railyards and these heavy-duty trucks.”

Industry concerns about current infrastructure, tech and costs

The trucking industry has some big concerns about these changes. Among them:

- Major gaps in charging infrastructure

- The new technology of electric trucks that can’t yet make needed distances

- There's also the fact these trucks can be three times as expensive as traditional trucks.

But already companies are making the transition successfully — it just requires a lot of planning ahead.

Shane Blanchette is a vice president with distribution company QCD, which primarily does “last-mile” deliveries for its parent company Golden State Foods. Here in Southern California it delivers to Starbucks, primarily with heavy-duty tractor trailers, with most deliveries within 120 miles (which current technology can handle).

Already, it's well on its way to transitioning its Southern California fleet of 74 trucks to electric trucks made by Volvo. And, he said, his drivers like the quieter, smoother vehicles. They also require a lot less maintenance (e.g. no oil changes or high fuel costs).

“We think this is actually a competitive advantage as we continue to transition,” Blanchette said.

-

At magnitude 7.2, buildings collapsed

-

Now spinning in front of Santa Monica apartments

-

Advocates seek end to new LAUSD location policy

Financial assistance is available

Blanchette said QCD was able to afford these electric trucks through funding from Southern California Edison (SCE) and other partners. They also received support from SCE to upgrade charging infrastructure at their Fontana location.

He said he expects the electric trucks to even further save the company costs down the line. For example, at their La Puente location, the company is taking an innovative approach to charging needs by building a microgrid (a self-sufficient, miniature power grid). Blanchette said it will offset utility bill costs and release strain on the power grid, which will have to deal with a much higher demand for power as the electrification transition accelerates. Their microgrid will have solar panels and battery storage that will allow the company to charge 30 trucks at a time at least — without straining the broader power grid we all rely on.

What's next

There’s no question there are a lot of challenges ahead for the industry, but there’s a lot of opportunity too, said Lawren Markle, communications lead for Santa Monica-based clean transportation consulting firm GNA.

“This is going to be a challenge for fleets, it requires a lot of lead time, great partners, and thoughtful analysis of what routes you want to run because there are some range issues at this early stage of the market,” Markle said. “Are there still challenges? Yes. But the industry’s working to overcome those.”

“It’s probably the biggest transition in transportation since we went to gas-powered cars. It’s not something to take lightly and it’s going to take a lot of work,” Markle added.

-

The state's parks department is working with stakeholders, including the military, to rebuild the San Onofre road, but no timeline has been given.

-

Built in 1951, the glass-walled chapel is one of L.A.’s few national historic landmarks. This isn’t the first time it has been damaged by landslides.

-

The climate crisis is destabilizing cliffs and making landslides more likely, an expert says.

-

Lifei Huang, 22, went missing near Mt. Baldy on Feb. 4 as the first of two atmospheric rivers was bearing down on the region.

-

Since 2021, volunteers have been planting Joshua tree seedlings in the Mojave Desert burn scar. The next session is slated for later this Spring, according to the National Park Service. Just like previous times, a few camels will be tagging along.

-

There are three main meteorological reasons why L.A. is so smoggy — all of which are affected when a rainstorm passes through and brings clearer skies.