Walk around Los Angeles and you might notice a remnant of the early days of the automobile: a set of stairs, typically fenced off and locked, leading down to a tunnel below a busy road.

Dozens of these underground passages can still be spotted across the city.

At one point, L.A. had more than 200 pedestrian tunnels, many of them built in the 1920s and ‘30s, according to the Los Angeles Times.

So how many exist today? According to city records, L.A. currently owns and maintains 91 tunnels — most of them dating back to the early 1950s through late 1970s, said Mary Nemick, director of communications for L.A.’s Bureau of Engineering. But she noted “there are a few [from] the 1920s and a few unknown.”

As far as how many are still used, that’s a bit of a mystery — Nemick said her department “cannot determine” that number.

“Our records show many are closed … with sand or cement slurry poured in and capping off the tops at both ends,” she said. “These closures are due to safety reasons and all were initiated by the council district.”

Nemick declined to elaborate on those “safety reasons,” though local news stories in recent years point to dirty, dangerous conditions and concerns over unhoused people living in some tunnels.

Accessible or shuttered, these tunnels provide a valuable look back into L.A.’s history of traffic violence — and a reminder of how that history is repeating itself today.

From A ‘Plaything’ For The Wealthy To A Revolutionary Vehicle

The car culture we take as a given today in L.A. — and across the U.S. — is the result of strategic policies and public relations directed by early automakers and the auto clubs that championed them.

Let’s step back in time.

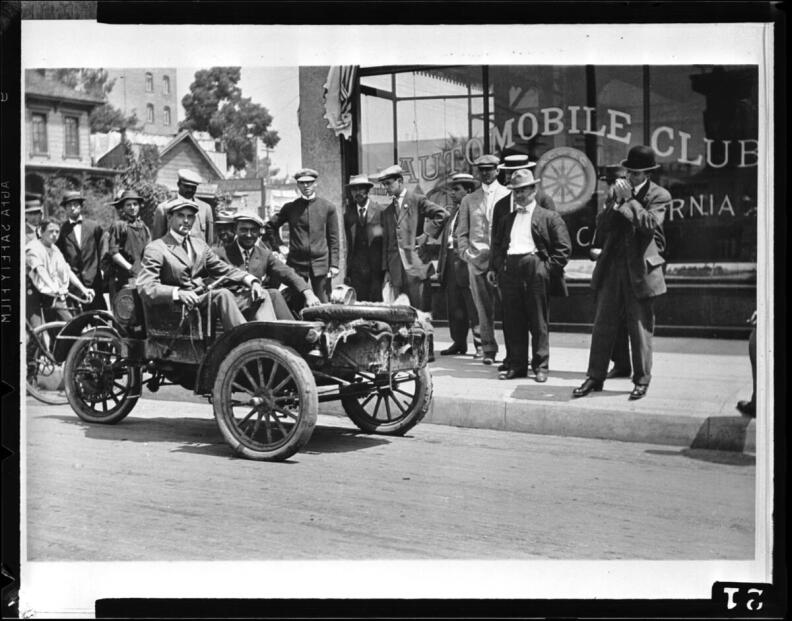

In 1900 the Automobile Club of Southern California formed. At first, the club was essentially for wealthy members. That’s because cars were “exceedingly expensive,” explained Morgan Yates, corporate archivist for the Auto Club.

“They were really more of a plaything, kind of a rich person's toy,” he said. “They hadn't achieved [the] level of utility that they did later on.”

-

At magnitude 7.2, buildings collapsed

-

Now spinning in front of Santa Monica apartments

-

Advocates seek end to new LAUSD location policy

That started to change in the 1910s, when Henry Ford’s innovations made cars attainable for more Americans. As those costs came down, Yates said the local auto club became focused on what it could do "to make life better for people who own automobiles.”

And that rising number of drivers wanted to go faster and farther. So auto clubs focused on getting more roads paved, posting street signs and producing maps. By the late 1910s, the Automobile Club of Southern California was the largest in the nation — and still is today, Yates said.

To amend a famous phrase by French philosopher Paul Virilio: when you invent the car, you also invent the car crash. And in the early 20th Century, there were a lot of crashes.

How Bad Was It?

It was a national crisis (déjà vu, right?). Drivers in early 1900s were killing a lot of people — especially children.

At the time, playing in the streets was common; they were vibrant, public spaces teeming with people walking, biking and taking transit. The automobile brought disruption and destruction.

Society had to grapple with a “new machine that was on the roads that moved with speed, that had weight that was potentially quite dangerous to those around it and using them,” Yates said.

So dangerous that tens of thousands of people were killed each year. Roughly 75% of the victims were pedestrians and half of those victims were children, according to Peter Norton, associate professor of history at the University of Virginia’s Department of Engineering and Society.

“This was a public relations nightmare for the people who wanted to sell cars,” said Norton, who has studied the history of automobiles extensively and written two books — Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City and Autonorama:The Illusory Promise of High-Tech Driving.

The fault at the time, said Norton, was “overwhelmingly going to go to the driver.“ After all, that was the person “operating the dangerous machine.”

By the 1920s, the crisis of traffic violence had permeated the culture. (Remember the role cars and crashes played in The Great Gatsby?) Newspapers reported on the high rate of killings and published cartoons depicting drivers as grim reapers, mowing down pedestrians.

Looking at L.A. in 1924 alone, 38 children under age 15 were killed by drivers in the city and more than 1,000 were injured, the L.A. Times reported at the time.

Automakers and their interest groups scrambled to improve their image. They took advantage of their influence over political leaders to create preferential traffic laws. And they coordinated a national effort to shift the blame for traffic deaths to pedestrians and criminalize so-called “jaywalking.”

Miller McClintock — a man Norton calls “the nation’s first traffic expert” — played a major role in shaping early traffic laws in L.A. and beyond. With financial backing from the automaker Studebaker, McClintock drafted a new slate of traffic laws, which were adopted by L.A. Those rules then became a template for other U.S. cities.

History is written by the victors, and the auto industry clearly won control of city streets.

The ‘Great Separation’ Begins

Even as the press for the automobile started improving, more people were dying on L.A. streets.

Norton noted “there was never a time when people did not keep demanding safe access to the streets for pedestrians and for children,” including in Los Angeles.

"Mothers organized [and] picketed streets, demanding slower traffic and safer access to streets for pedestrians. And you never hear this, but it was persistent. And you never hear it in part because it was local, in part because it was women and in part because the people who tell the history of the automobile in this country have predominantly been the people who sell automobiles."

The increasing death toll sparked the idea for pedestrian tunnels, which Yates calls the “great separation” between people driving cars and everyone else.

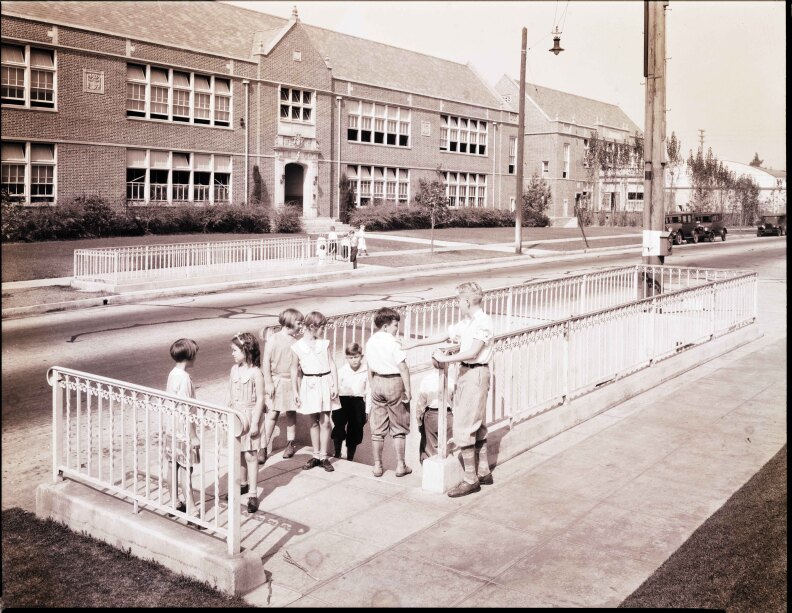

In the early days, the few tunnels that existed mostly ran under rail lines. Then in 1924, the first “experimental tunnel” designed specifically for children to avoid car traffic was built under Sunset Boulevard for students at Micheltorena Street Elementary, “at the request of the local parents and school officials,” Yates said.

“School kids in particular were able to pass below the traffic, and so there was no way that they could be hit,” he said. “[Tunnels] were viewed at the beginning as being something that was an expensive … but a very effective way to mitigate the dangers of crossing the streets.”

Not surprisingly, automakers and their supporters had a key role in the creation and expansion of L.A.’s pedestrian tunnel network. A 1925 bond measure approved by L.A. voters granted $350,000 (roughly $5.78 million today) to build more pedestrian tunnels across the city. It was initiated by the Automobile Club of Southern California, Norton said.

Later that same year, 46 tunnel sites near schools were approved by city officials. A decade later, federal infrastructure funding via the New Deal brought more money to construct tunnels in L.A. and the tunnel network grew.

Pedestrian Safety: Brought To You By The Auto Industry

As the idea for pedestrian tunnels gained momentum, it was Miller McClintock who oversaw the process of studying and selecting where those tunnels funded by voters in 1925 were built.

Sole credit for the tunnel idea isn’t with the auto club, Yates said, but the organization “provided expertise and served as a resource” to public agencies as they scrambled to rein in the mayhem automobiles brought.

Those tunnels are a physical sign of the fact that no longer was there going to be an expectation that the public authorities protect children's right to the city.

Initially, officials had some difficulty getting kids to cross streets by tunnel. Their solution was to require use of tunnels by pedestrians on streets where they were added.

And there was also a PR blitz. The Auto Club of Southern California launched campaigns targeted at children, with club representatives visiting schools to share club-created curriculum, posters and more.

“Once the kids were really kind of programmed to use the tunnels and encouraged to use them back and forth in school in particular, then it did appear that they were effective in reducing injuries to kids,” Yates added.

By the late 1920s, “practically every school in America was getting free safety curriculum from the American Automobile Association,” according to Norton.

“That curriculum had messages like: ‘streets are for cars, so stay out of them, never go in the street,’” he said. “To be fair, it probably saved kids’ lives. But the real gist of this safety education was that the automobile people have won — the street is for cars, children have to stay out.”

So why did the auto club take such an active role in pedestrian safety? Norton traced that to the “pretty shocking stand” L.A. took in the ‘20s that put car speed above everything else:

"L.A [was] early to decide that not only is driving a priority, but driving fast is a priority … At the time they're doing this in the rest of the country, the agreement is that driving fast is inherently dangerous and is the problem…There was a real notion in the early-to-mid '20s that speed kills, and that remedy for traffic casualties is just to slow cars down."

Slowing cars down, however, was bad for the auto business.

“As long as cities kept slowing cars down, people weren't going to be interested in buying cars, because that's their advantage over every other vehicle … their speed,” Norton said.

The question was, he said: “Do you restrict the drivers in favor of the pedestrians, or do you restrict the pedestrians in favor of the drivers?”

The ‘Exile’ Of Children

By the late ‘20s in L.A., Norton said that question was “pretty settled.” Cars over pedestrians — literally. Saving children’s lives while not slowing down car traffic was a major win-win for the auto industry, he explained.

"The beauty of tunnels was children would retain their access to the school, but no driver would ever have to slow down for the child crossing the street in a tunnel — they'll just speed along right over them."

The tradeoff, he said, was “exile from the streets” for children.

A century ago, a city where children needed to be taken everywhere would’ve been considered a “dystopian” nightmare, Norton explained. At the time, children walked and rode their bikes everywhere. But dangerous streets made that fraught.

“Those tunnels are a physical sign of the fact that no longer was there going to be an expectation that the public authorities protect children's right to the city,” he said. “Children will not have any independent access to anything — they'll have to be driven everywhere, at least until they're teenagers.”

Jessica Meaney, a mobility activist, said it’s obvious “the decision to do the tunnels was a decision to not impede drivers.”

“No one ever wants to inconvenience single-occupancy vehicles, but will inconvenience and tragically kill, harm, [and] impact families and individuals,” she said.

Meaney is the executive director of Investing in Place, a nonprofit advocating for better, more equitable infrastructure. For her, the tunnels represent a loss of public space that continues to affect Angelenos today.

“If we give up on our sidewalks,” she said, “and the only way we think things are going to be safe is if our kids go in these underground tunnels and avoid a vibrant street life … and all of the things that the sidewalk and our public space of Los Angeles can give to us, I think that's a mistake.”

What Happened To The Tunnels?

At first, the public seemed to like the tunnels, according to Yates, but their ultimate fate was “perfectly predictable.”

Those tunnels were another pricey piece of infrastructure to maintain and, as they fell into disrepair, the city traded one safety problem for another: “crime, grime and vandals,” Yates explained.

The tunnels could be dark, dank and dirty — not a welcoming space for pedestrians, especially children, who might encounter human waste or someone intending to harm them.

“Nobody wants to be underground in a situation like that,” Yates said.

The tunnels were also a heavy lift, both literally and financially.

“It's not easy to excavate and then put in all the masonry, all the concrete necessary to make those have the drainage they need, perhaps have lighting, have the ventilation they need,” Norton said. “And the priority was for the motorists, so the money was going primarily in that direction.”

Auto interest groups and city officials did consider other options, including rebuilding cities with elevated sidewalks, where people could walk safely above car-filled streets. Those concepts mostly stayed concepts (if tunnels were too expensive, can you imagine the cost to lift all the sidewalks?), though the idea was adapted for the pedestrian walkways / cages we see arched over freeways today.

As communities raised concerns about safety in the tunnels, the city started to close many of them. Eventually, that included the inaugural school tunnel near Micheltorena Street Elementary on Sunset, which was closed and filled with cement in 2017.

We dedicated a pedestrian safety improvement next to Micheltorena Elem on Sunset Blvd #SilverLake. Closing the adjacent tunnel will eliminate blight, and enhance the overall safety and walkability in the neighborhood. #CD13 pic.twitter.com/JoeRC87xiv

— Mitch O'Farrell (@MitchOFarrell) November 27, 2017

Norton said he isn’t surprised how the safety experiment turned out.

“When your solution to protecting somebody is to set them aside in a marginalized place of any kind, those places tend to be vulnerable,” he said. “A tunnel is almost inherently a dark and possibly menacing place. To me, it feels like a pretty obvious sign that your city's priorities are clearly for the drivers at that point.”

Though a fraction of L.A.’s 220-plus tunnels still exist today, some are still used to provide safe passage to students as they were designed to do nearly a century ago.

An ‘Essential’ Tunnel In Eagle Rock

On a recent weekday morning, I visited Colorado Boulevard near Floristan Avenue in Eagle Rock.

Dahlia Heights Elementary School sits on the corner and I watched dozens of children, most accompanied by a parent, disappear below street-level on the opposite side of busy Colorado Boulevard and emerge near the campus via a still-used tunnel.

City records show it was built around March 1932.

This tunnel isn’t as dark and dreary as others can be; all the light bulbs are working and a colorful mural covers the walls and up the stairs, thanks to a 2018 project by students and a local artist.

The tunnel entrances are locked for most of the day, since its use is aimed toward students. Nemick, of the city’s engineering bureau, said her department provided a copy of the key to the school’s principal, who entrusts it to custodial staff.

School staff unlocks the tunnel gates in the mornings and locks up later in the afternoon. They also handle basic cleanliness, such as keeping the tunnel clear of dirt, leaves and trash, but sometimes have to call on the city to address flooding and lighting issues, along with the occasional graffiti.

One parent who gave only his first name, Sergio, said the tunnel is a great feature for getting across Colorado, especially with the way people drive.

“With the [134] freeway exit and the downhill action going on here, sometimes they blow through this light,” he told me, referring to the intersection at Colorado and Floristan. He has two kids at Dahlia Heights.

Fellow parent Mary O’Connor said she uses the tunnel with her kids every day to cross “super dangerous” Colorado Boulevard.

“People run that red light all the time,” she said. “Using the tunnels is essential and it's also really fun for them because it's painted and it's an adventure, really.”

Ellen Mackle walks with her two kids to Dahlia Heights and uses the tunnel most days. The tunnel occasionally contains “surprises,” she noted, such as human feces. She believes it’s the safest option to protect pedestrians — especially children — from drivers, but points out that it’s not accessible for everyone.

“Anyone with any mobility issues can't use it, and so they're stuck either crossing at Lolita or Townsend — both of which are pretty scary places,” Mackle said. “I think the parents feel like they can't let their children have any independence in town because of the vehicle traffic.”

In Mackle’s ideal L.A., “there would not be high-speed arterials intersecting residential neighborhoods.” She’d love to see changes that would slow drivers down and make streets more equitable for walkers.

“I would like to have more pedestrian areas,” she told me. “Although this is L.A. after all —I don't know if that's really possible."

The Cycle Of Traffic Violence Continues

That summation — it’s L.A., what can you do? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ — is understandable when you consider our history.

More than 100 years after those initial efforts to keep pedestrians safe from dangerous drivers, streets across the nation mostly look the same. As a result, the death toll continues to rise. Last year marked a 16-year high for traffic deaths nationally.

A variety of safety programs have been launched — just like in those early days — but tangible progress to make streets safer has not happened. (I’ve spent a lot of digital ink explaining why.)

In 2015, L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti launched the city’s version of Vision Zero — an international safety movement that aims to eliminate traffic deaths. But between 2015 and 2021, traffic deaths rose 58% overall. Of the more than 1,700 people killed in that time period, roughly half were pedestrians.

And L.A. streets are on pace to be even deadlier by the end of 2022 — especially for pedestrians. Preliminary city data shows 63 pedestrians have been killed this year through May 14. That’s an increase of 54% from the same period last year.

Nationwide, traffic collisions have been the leading cause of death for children for decades (until 2020, when gun deaths became No. 1, according to researchers).

To Norton, the lack of safety on our roads and our typical reaction to traffic deaths are not coincidences.

“One of the signs of the success of the automobile people is that today, when a pedestrian is struck and killed, we usually either think of it as a terrible misfortune, or even as the pedestrian’s fault — especially if it's a child, we're likely to blame the parents,” he explained. “This is one of the reasons why these automotive interest groups organized not just to shift the street design and put in tunnels, but also to shift laws and social norms. It was a combination of all three to make this work.”

Jessica Meaney, the mobility activist, said the result is large “super-fast moving cars” and land-use choices that force people into cars to get around.

"That contributes to why it's so dangerous for our children to be out on our sidewalks,” she said. “Public space is broken and it has been broken for a long time."

-

1928 image courtesy courtesy Auto Club of Southern California archives; present-day photo by Ryan Fonseca; treatment by Dan Carino

-

Restored with care, the 120-year-old movie theater is now ready for its closeup.

-

Councilmember Traci Park, who introduced the motion, said if the council failed to act on Friday, the home could be lost as early as the afternoon.

-

Hurricane Hilary is poised to dump several inches of rain on L.A. this weekend. It could also go down in history as the first tropical storm to make landfall here since 1939.

-

Shop owners got 30-day notices to vacate this week but said the new owners reached out to extend that another 30 days. This comes after its weekly swap meet permanently shut down earlier this month.

-

A local history about the extraordinary lives of a generation of female daredevils.

-

LAist's new podcast LA Made: Blood Sweat & Rockets explores the history of Pasadena's Jet Propulsion Lab, co-founder Jack Parsons' interest in the occult and the creepy local lore of Devil's Gate Dam.