What You Didn’t Know About Bruce Lee’s Life In Los Angeles

In 1966, Bruce Lee was an exciting young martial artist from Hong Kong — a volcano of speed, skill and swagger who had caught the eye of Hollywood producers.

As acting opportunities began to emerge in Los Angeles, Lee and his young family left Oakland, where he’d been running a martial arts school.

One of their first apartments in L.A. was at the Barrington Plaza, a trio of gleaming white towers on the Westside.

Rent for their two-bedroom was more than a touch out-of-reach for Lee, even though he had landed a supporting TV role on a new ABC show, “The Green Hornet.”

“[My parents] could not actually afford the rent there,” said Lee’s daughter, Shannon. “So they bargained with the property manager to reduce their rent in exchange for kung fu lessons.”

The arrangement wouldn’t last.

“They got kicked out when it was discovered by the property owner that the property manager had been cutting all these side deals with the tenants,” Lee said.

-

At magnitude 7.2, buildings collapsed

-

Now spinning in front of Santa Monica apartments

-

Advocates seek end to new LAUSD location policy

Just a few short years after this setback, Lee would break through as one of the world's biggest international action heroes with star turns in a string of Hong Kong blockbusters.

His shocking death at age 32 was even more sudden.

Thursday marks 50 years since Lee died from cerebral edema on July 20, 1973, weeks before his most famous and influential film, “Enter The Dragon,” opened in the U.S. Its success set off a martial arts craze, while shattering stereotypes of the submissive Asian.

Even in death, Lee is still one of the most famous Asian Americans, with a fandom spanning cultures and generations that embraces his films and philosophy exploring personal growth and adaptability.

Lesser known about Lee are his years in L.A., before he left for Hong Kong in 1971 to take the lead roles that eluded him in Hollywood – a period filled with exhilarating moments but also struggles.

After the family was forced to leave the Barrington, they bounced around to homes in Inglewood and Culver City before settling in Bel Air.

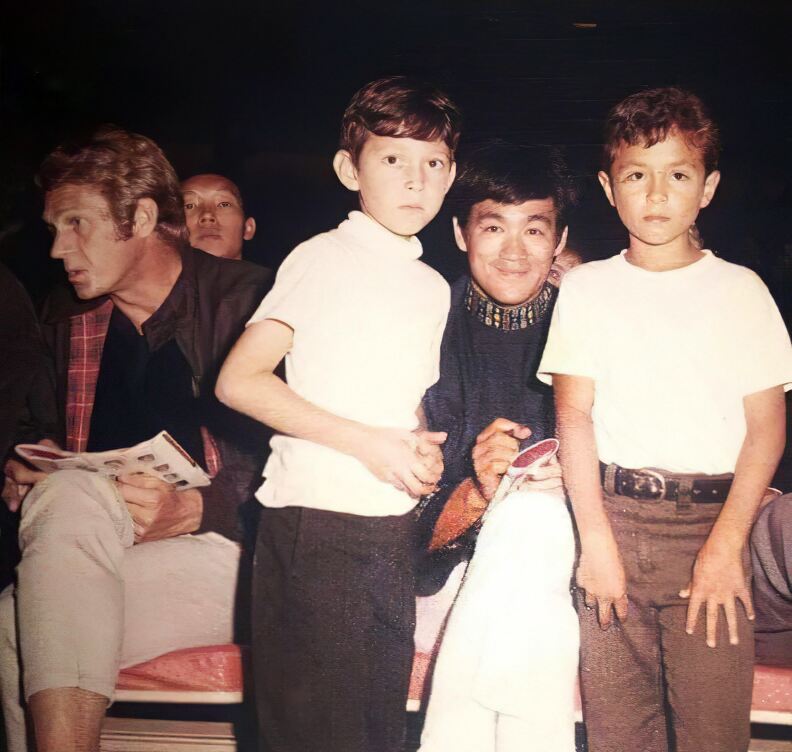

To Lee’s disappointment, The Green Hornet ended after only one season, so he pivoted to working on sets as a fight choreographer. He also became a trainer to such stars as Kareem Abdul-Jabar and Steve McQueen, who became close friends.

Lee didn’t just stick to Hollywood, he befriended a wide cross-section of Angelenos. He opened a studio in Chinatown where he taught Jeet Kune Do, a style of martial arts he developed.

He could also be spotted at dances organized by Chinese American college and grad students. A teenage cha-cha champ in Hong Kong, Lee whirled around partners like Gay Yuen, who studied at UCLA and ran in the same social circles.

“When the band would take a break, he would show off his martial arts moves, his strength and his skills,” Yuen said, recalling how Lee would get down on the dance floor to demonstrate one of his signature feats, the two-finger push-up.

Decades later, Yuen is the board chair at L.A.’s Chinese American Museum, which is presenting an exhibition timed to the anniversary of Lee’s death. Featured is a life-sized statue of him that will be donated this week to the Bruce Lee Foundation run out of L.A. by his daughter.

Elsewhere in L.A., Lee’s legacy is on display through murals and the seven-foot-tall bronze statue installed in Chinatown’s Central Plaza on the 40th anniversary of his death in 2013.

The tributes serve as reminders of Lee’s ties to the city, a place where he planned to return after conquering the Asian box office.

“We left our dog here and everything when we went to Hong Kong,” recalled Shannon Lee. “Once [my father] had accomplished what he wanted to accomplish there, the idea was to move back and continue to pursue films.”

A life-changing invitation

Lee hadn’t started out seeking out a film career in the U.S. or to become an Asian American trailblazer.

Yes, Asian American. While primarily recognized as being from Hong Kong, Lee was born in San Francisco to parents who’d been touring the U.S. with a Chinese opera troupe.

He was raised in Hong Kong, and coming from a showbiz family, fell into acting as a child, racking up roles in some 20 films. But when he moved back to the country of his birth at age 18, his focus had switched to teaching martial arts. Having trained under kung fu masters in Hong Kong, Lee was thinking about starting a chain of self-defense schools.

In 1963, Lee opened his first school in Seattle, where he had studied philosophy at the University of Washington and met his wife, Linda.

The second school was in Oakland, where he was living at the time he got a life-changing invitation in 1964.

Celebrity karate master Ed Parker asked him to showcase his skills at a tournament in Long Beach.

At the inaugural International Karate championships, a rapt audience inside the Long Beach Municipal Auditorium watched Lee debut the one-inch punch:

Applause filled the auditorium as Lee effortlessly performed two-finger push-ups.

Entree into Hollywood

Lee’s explosive strength and precision left a strong impression on a particular martial arts enthusiast in the crowd. Jay Sebring was a celebrity hairstylist who famously dated the actress Sharon Tate. His high-powered clients included a Hollywood producer named William Dozier who was looking for a young Asian male to play the son of the fictional detective Charlie Chan.

Sebring enthusiastically recommended Lee for the role and in 1965, Lee traveled from Oakland to the 20th Century Fox studio for a screen test, where he demonstrated kung fu moves on an unsuspecting crew member.

It was Lee’s first foray into Hollywood, thanks in no small part to Sebring.

Several years later, the hairstylist would forever be entered into lurid Hollywood lore: he was among those murdered by the Manson family in the summer of 1969, along with Tate.

Man About Town

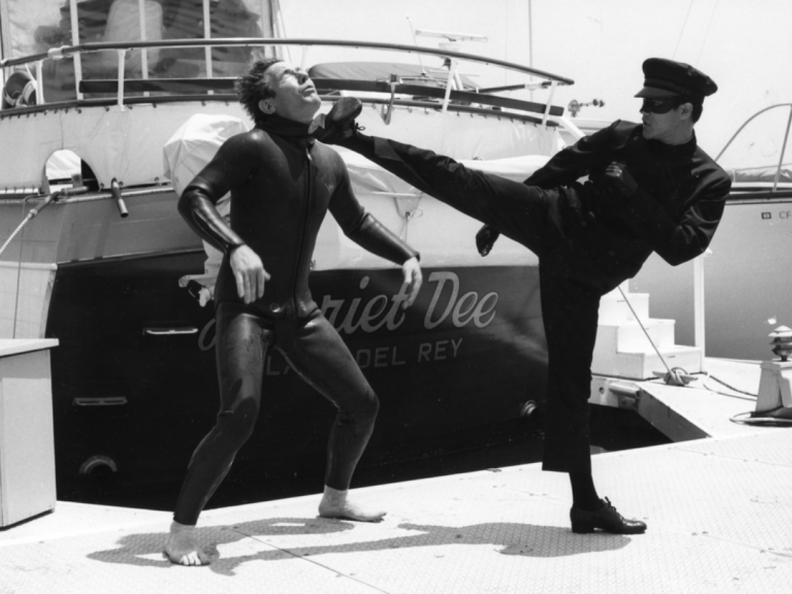

The Charlie Chan spinoff never got made. Dozier, the producer, instead secured Lee a supporting role on The Green Hornet as Kato, the masked crime-fighting valet to the titular hero.

The ABC show lasted only one season, running from 1966 to 1967. But being on the first of many Hollywood sets offered invaluable lessons, Lee’s daughter said.

“In Hollywood, he learned a lot about process, filmmaking and scriptwriting and camera angles and shots, which informed his ability to make the movies in Hong Kong later,” Shannon Lee said.

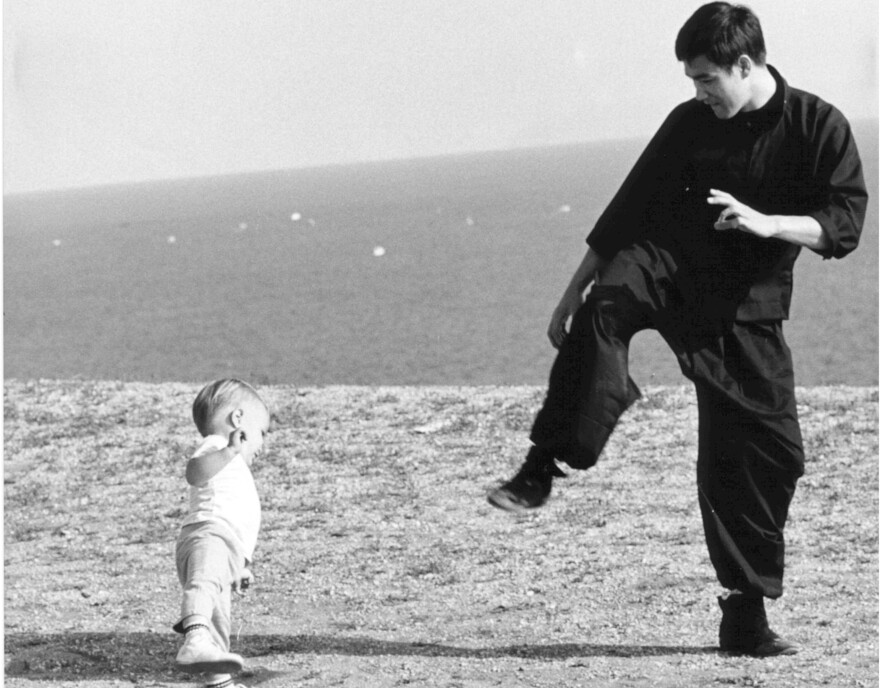

Post-Kato, Lee stayed in the Hollywood orbit, choreographing fights on film sets and teaching martial arts to celebrities. He earned enough money to buy a ranch in Bel Air, where his family would live until they relocated to Hong Kong in 1971.

He also spent a lot of time in Chinatown, where people spoke his native Cantonese and the dim sum tasted like home. His daughter said he got his hair cut by a barber named “Little Joe” for years.

It was on College Street that Lee opened his third martial arts school in 1967. The students were a tight-knit group who would dine together in Chinatown after training, his daughter said. They would also train with Lee at his homes, mingling with celebrity students like Abdul-Jabbar.

Yuen of the Chinese American Museum said among the young people who used to hang out in Chinatown, Lee was known for having been on TV and being particularly advanced in martial arts. Other than that, “he was just like another person in the group," Yuen said.

“It wasn't like, ‘Wow, Bruce Lee,’ right?” Yuen said. “The boys would be challenging him and go ‘Hey, when are we going to fight?’ and they’d spar, kiddingly.”

Only when she stops to think about it does Yuen realize how surreal it is to see someone from her youthful past become a global cultural icon, one that her museum is honoring as a symbol of strength in the face of anti-Asian violence and discrimination that persists today.

“There's someone like Bruce Lee, who says 'We're going to fight back,'” Yuen said. “And for that, we’re thankful.”

-

Known for its elaborate light displays, this year, the neighborhood is expecting a bigger crowd tied to the release of “Candy Cane Lane” on Amazon Prime Video.

-

Dancers at Star Garden demanded better working conditions — including protection from aggressive guests. Up next: An actual contract.

-

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers rejected the SAG-AFTRA union's request for a separate type of residual payment that actors would get once their programs hit streaming services.

-

Sarah Ramos says she actually likes self-taped auditions, but without regulations: “This is a strain on our resources, a strain on our community and it's untenable.”

-

Actor Erik Passoja said his digital likeness was used in a video game without his consent.

-

The Theatricum Botanicum was a safe spot during the McCarthy era, served as a temporary home to folk singer Woody Guthrie, and staged countless productions of A Midsummer Night's Dream.