Proposition 187: Why a Ballot Initiative That Passed In 1994 (And Never Went Into Law) Still Matters

-

A state initiative passed in November 1994 to stop immigrants without legal status from accessing public school, medical care and other services. This story is part of our series looking back at Prop 187's legacy, and how it's still felt in modern day L.A.

California voters approved a ballot initiative which sought to deny public services to immigrants living in the U.S. without legal status on Nov. 8, 1994. To this day, Proposition 187 remains one of the most divisive measures in state history, and the battle over its passage ultimately reshaped California politics.

For those who couldn't prove they and their children were U.S. citizens or legal residents, Prop 187 cut off access to:

- Non-emergency public health care

- Elementary, middle and high school education

- Public colleges and universities.

The initiative also required state and local agencies to report immigrants who didn't meet residency criteria to both state officials and federal immigration authorities.

In November 1994, Proposition 187 passed with nearly 59% of the vote — but its controversial provisions were never implemented. Following a series of legal challenges, the measure was declared unconstitutional by a federal judge in 1997.

-

At magnitude 7.2, buildings collapsed

-

Now spinning in front of Santa Monica apartments

-

Advocates seek end to new LAUSD location policy

Proposition 187 and its aftermath marked a turning point in California history. Political scientists and analysts draw a direct line from the passage of Prop 187 to a shift in the state's political identity. The state that was home to Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan went from a GOP stronghold to the solidly Democratic territory it is today.

The Background

Prop 187 came at a time when California was just beginning to emerge from a deep recession that cost the state hundreds of thousands of jobs.

Conceived of by an out-of-work Orange County accountant, Ron Prince, and a husband-and-wife political team, the measure's co-authors also included then-Assemblyman Dick Mountjoy, a conservative Republican from Arcadia. Mountjoy was reportedly responsible for suggesting that the initiative be a ballot measure rather than a piece of legislation.

Prop 187 — also known as "Save Our State" — claimed in its text that Californians were "suffering economic hardship" due to the presence of immigrants who lacked legal status, and sought to cut them off from public services. Among its key provisions:

- Anyone who could not provide evidence that they were a U.S. citizen, legal resident, or someone "lawfully admitted for a period of time" would not have access to public social services, non-emergency public health care services, or public schools. Post-secondary education would also be off limits.

- Children whose parents were unable to provide citizenship documents would be kicked out of public schools after 90 days, the initiative noted, in order to "accomplish an orderly transition to a school in the child's country of origin."

- Teachers, health care workers and law enforcement were responsible for monitoring and reporting individuals who did not meet the requirements of the measure. Public service agencies would be required to report immigrants who could not prove their legal status to the California Attorney General and with federal immigration officials, then known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

- California law enforcement agencies would be required to "fully cooperate" with the Immigration and Naturalization Service, regarding people arrested who were suspected of being in the country illegally.

The measure's purported goal was to save money for California, although opponents warned that Prop 187 could endanger the state's federal funding, and that there would be implementation costs.

As the initiative's authors worked to generate support, then-Governor Pete Wilson (R) was running for re-election against then-state treasurer Kathleen Brown (D), who was leading in the polls.

Wilson was already airing controversial campaign ads that directly targeted illegal immigration to the U.S. from Mexico. The 30-second spots featured grainy, black-and-white footage of individuals running across the Mexican-American border as a man's ominous voice opined: "They keep coming."

By the time Prop 187 qualified for the ballot in July 1994, Wilson was ready to throw his weight behind it.

Before The Vote

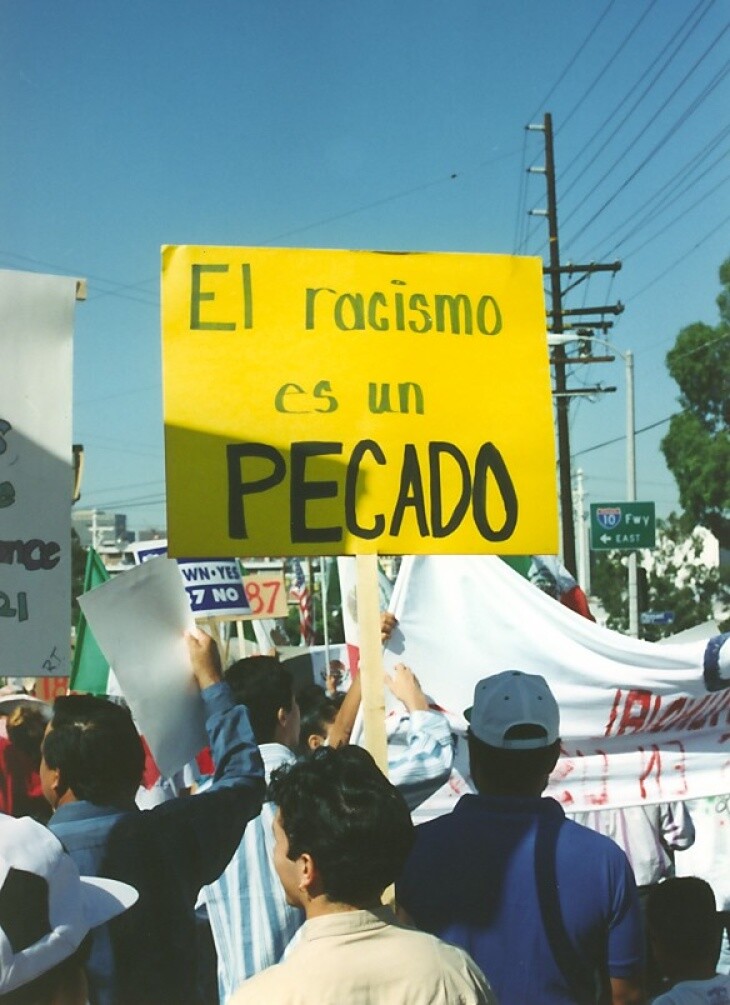

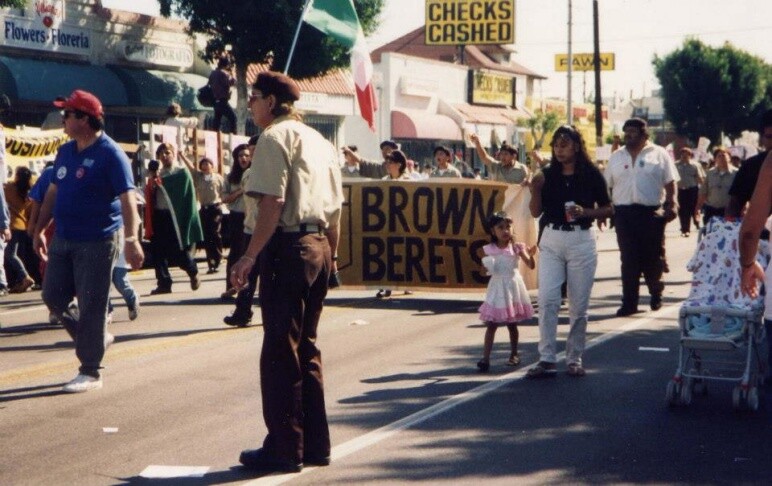

Voters were deeply divided over Prop 187, even in immigrant communities. But in the months leading up to Election Day, Los Angeles activists, students and residents who saw the measure as anti-immigrant and, more specifically, anti-Latino began to agitate against it.

Nevertheless, during a debate with Brown on Oct. 16, 1994, Wilson didn't back down. When asked if he would be able to "look [a] second-grader in the eye and call the INS," he replied:

"I make no apology for putting California children first...Yes, those children who are in the country illegally deserve an education, but the government that owes it to them is not in Sacramento or even in Washington. It is in the country from which they have come."

That same day, a large, vocal opposition to Prop 187 made its voice heard as well —approximately 70,000 people marched through DTLA in protest of the measure.

Students soon followed suit. Angel Cervantes was a graduate student at the time, and helped formed a group called the Four Winds Student Movement.

"[We] wanted to get involved and begin to organize mass demonstrations, walkouts, teach-ins," he said. "We began to hold meetings for high school students, because... we felt that if they're going to [protest], they should be as informed as they could."

Their efforts were a success. On Nov. 2, 1994, 10,000 students from over 30 LAUSD schools got up from their classrooms and took to the streets.

"It was the biggest thing I had ever seen, probably one of the most life-changing empowering, moments," said Cervantes. "To see so many groups, so many organizations, so many banners, so many different Latin Americans... it was very powerful."

The Vote

Despite this effort, Proposition 187 passed on Nov. 8, 1994 with nearly 59 percent of the vote. But the fight against it was only beginning.

Several anti-Prop 187 groups challenged the measure with lawsuits immediately, including the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation. On Nov. 16, U.S. District Court Judge W. Mathew Byrne issued a temporary restraining order against the initiative's implementation.

Altogether, five lawsuits would be filed challenging the measure. On Dec. 14, 1994, U.S. District Court Judge Mariana Pfaelzer issued a preliminary injunction, blocking implementation on a majority of the measure's provisions.

In Jan. 1995, the state pushed back, filing an appeal against the injunction in San Francisco Superior Court.

But it was too late - the injunction was upheld, and in Aug. 1996, President Bill Clinton signed a new welfare reform law which strengthened the argument against Prop 187.

Judge Pfaelzer ruled that the measure was unconstitutional in Nov. 1997, and almost two years later, in Jul. 1999, Proposition 187 was effectively overturned via federal mediation.

Inadvertently, Prop 187 - which was largely backed by Republicans - activated a tidal wave of new Democratic voters and leaders, including new Latino elected leaders, as it pushed Latinos away from the GOP.

A 2013 report from the Latino Decisions polling research firm concluded that between 1994 and 2004, California registered an estimated 1.8 million new voters, 66 percent of whom were Latino, and 23 percent of whom were Asian. During that time, the growth rate of Latino registered voters in the state far outpaced the growth rate of its Latino population.

In 1994, elected positions in California were split nearly equally down party lines; approximately 50% Democrat and 50% Republican, according to data compiled by Loyola Marymount University. Since that year, those numbers have shifted dramatically; as of 2018, approximately 80% of elected positions in the state of California were held by Democrats, and 20% were held by Republicans.

In September 2014, then-Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill repealing the unenforceable provisions of Prop 187, essentially striking the initiative's language from the books.

Years later, however, the debate over immigrants and public benefits continues on the national stage, as the Trump administration has proposed disqualifying immigrants from obtaining green cards under what's become known as the "public charge" rule if they use public benefits such as health, food and housing assistance, or may use them in the future. The rule has been blocked in court for now.

Nevertheless, for many who marched in favor of immigrant rights 25 years ago, the messages of hope and unity still resonate to this day.

"The walkouts and mass movement that occurred, changed my life," said Cervantes. "I saw firsthand when people organize themselves, when even kids, youth decide that they're going to take a take a stand on a political issue, they can make a big difference."

Timeline

Jul. 1994: Proposition 187 qualifies for the ballot.

Oct. 16, 1994: Governor Pete Wilson, running for re-election, debates state treasurer Kathleen Brown in the gubernatorial race. Wilson says that neither the state nor the country owe an education to children in the country without legal immigration status.

On the same day, 70,000 people march through DTLA to protest Prop 187.

Nov. 2, 1994: 10,000 students from over 30 LAUSD schools participate in a school walkout in protest of Prop 187.

Nov. 8, 1994: Proposition 187 passes with nearly 59 percent of the vote.

Nov. 16, 1994: U.S. District Court Judge W. Matthew Byrne issues a temporary restraining order against the implementation of Prop 187.

Nov. through Dec. 1994: Five lawsuits are filed challenging the measure.

Dec. 14, 1994: U.S. District Court Judge Mariana Pfaelzer issues a preliminary injunction, blocking implementation on a majority of the measure's provisions.

Jan. 1995: The state of California files its own lawsuit in San Francisco Superior Court and - separately - appealing Judge Pfaelzer's preliminary injunction. The injunction is later upheld.

Aug. 22, 1996: President Bill Clinton signs a new law which strengthens opponents' legal argument against Prop 187.

Nov. 14, 1997: Judge Pfaelzer rules that the measure is unconstitutional.

Jul. 29, 1999: Prop 187 is effectively overturned through federal mediation.

Sept. 15, 2014: Governor Jerry Brown signs legislation repealing unenforceable provisions of Prop 187 and removing its language from state codes.

-

The severe lack of family friendly housing has millennial parents asking: Is leaving Southern California our only option?

-

As the March 5 primary draws closer, many of us have yet to vote and are looking for some help. We hope you start with our Voter Game Plan. Since we don't do recommendations, we've also put together a list of other popular voting guides.

-

The state's parks department is working with stakeholders, including the military, to rebuild the San Onofre road, but no timeline has been given.

-

Built in 1951, the glass-walled chapel is one of L.A.’s few national historic landmarks. This isn’t the first time it has been damaged by landslides.

-

The city passed a law against harassing renters in 2021. But tenant advocates say enforcement has been lacking.

-

After the luxury towers' developer did not respond to a request from the city to step in, the money will go to fence off the towers, provide security and remove graffiti on the towers.