'Black Enough?' Mixed Musings On My Skin Color, Hair, and Heritage

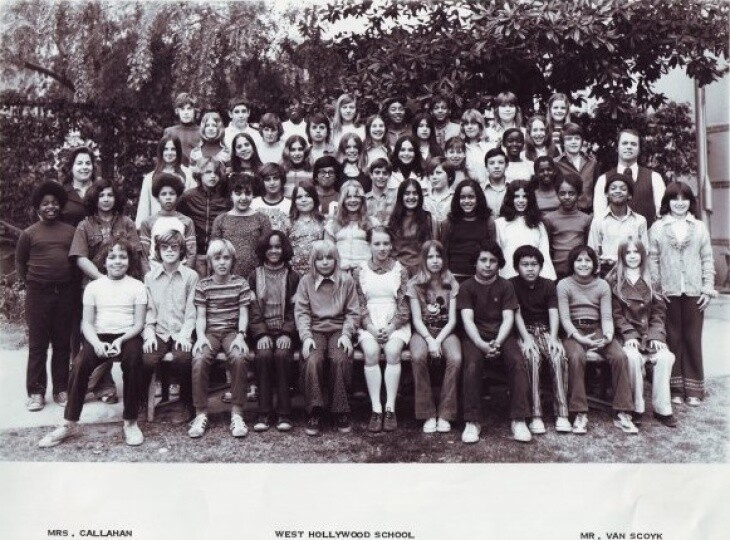

The first time I was ever called "high yellow" to my face was in fifth grade, at West Hollywood Elementary School.

We had just moved there from the Mid City area, and while the school was just as multicultural as my previous one, it wasn't until then that I learned some of my people just ain't gonna like me because my skin and hair aren't enough like theirs.

-

From June 2020 to July 2021, we published your stories each week to continue important conversations about race/ethnicity, identity and how both affect our lived experiences. We now have a new series Being American, which is again soliciting your essays.

-

Read:

For two years, a small group of girls taunted me with "You think you cute!" and "You must be stuck up!" because of what they called my "light-complected" skin and my "good" hair.

Such concepts were foreign to me. Number one, I hadn't thought about my skin color or anyone else's all my years up to that point, so how could I be stuck up about it? Sure, they didn't look quite like me, but they did look like my mother, my uncle, my grandparents and my cousins, who were my best friends growing up. So I truly didn't understand the hostility, especially because I had never even dealt with it from white folks up to that point.

And number two, I hated my frizzy, brittle hair. Most of the time I wore it in a ponytail, except on annual picture day.

Even today, I only keep it long because my husband of 33 years likes it that way and it's a trade-off to make him keep his beard. That, and the pandemic.

The last time I was called "high yellow" to my face was two years ago, by a Black co-worker at my former job. Forget that this girl was as light as me.

Over the decades I've gotten used to the sprinkling of macro- and micro-aggressions from some of my own people about my skin tone and hair texture, and it's just funny to me at this point. Sort of.

Of course, being called "high yellow" in the workplace, of all places, was unexpected. The only other time something like that had happened was many years prior, when another Black co-worker said she wanted to snatch me in a dark alley and chop off all my hair. But here I was, much older and wiser this time, laughing out loud but also scrambling to show her photos on my phone of my beautiful chocolate family.

See? I must've been subconsciously thinking. Am I Black enough now?

Why did I feel a need to prove to her how Black I am? Probably because who doesn't want to feel the love from the very group of people one rightfully identifies with the most?

On the other hand, why do I, a "light-complected" mulatto, as some would call me, from West Hollywood, with a white Jewish stepfather and hair beyond my shoulders, identify as Black?

Well, because that's my ethnicity, my culture, and my personal family heritage.

THE BACKDROP

I know very little about my white biological father and that side of my lineage. He left before I was even five years old, and my memories of him are all bad and vivid. He and my mother met at an NAACP office in Detroit when she was still a teenager living with my grandparents and uncle in Detroit's historic Brewster Housing Project (aka Frederick Douglass Apartments).

He soon moved her away to Los Angeles, and they had five kids. My twin brother and I are the youngest.

My grandparents were civil rights activists in the 1940s, participating in picket lines and sit-ins at whites-only restaurants well before the movement gained national traction in the 1950s and '60s.

They were among the six million Black Americans who relocated from the rural South to the North, Midwest and West during the Great Migration. My mother was three years old then and couldn't understand why her piggy wasn't allowed on the bus.

Once they were settled in Detroit, education, activism and sociopolitical change were top priorities for them. In fact, that's pretty much all my grandfather talked and wrote about all the way up to his death in 2016, at 101 years old.

After what he had seen and fought for, it is quite remarkable that he lived to see a "Negro," a common term for his generation, win the presidency of the United States -- not once, but twice.

My uncle and his family also moved to L.A. We all lived in Pacoima, where my cousins were our regular playmates, until my mother and stepfather moved us to the city.

Both my uncle, my mother, and my Jewish stepdad were active in grassroots organizations.

I'm reminded of my very groovy parents' wedding at the Los Angeles Inner City Cultural Center. For the ceremony, they walked in together to the jazz version of "2001: A Space Odyssey" and had both a rabbi and a Black minister officiate. The reception buffet was Kentucky Fried Chicken with all the fixin's.

We kids went to either Wilton Place Elementary, John Burroughs Junior High or L.A. High until we moved to West Hollywood, closer to my mother's job with a local television station. My little stepbrother lived with his mother, but we saw him often. We lived there all through my years at Bancroft Junior High, Hollywood High, and UCLA.

MY SKIN

If anything good came out of those first taunts during my tween years, they did get me to start thinking about the gravity of racial issues, the unintended implications of my mixed ethnicity, the depth of my Black heritage, and the celebration of my increasingly multicultural extended family.

Those taunts, coupled with my grandparents' history of racial justice and sociopolitical activism, and emphasis on higher education, taught me how to embrace all of these realities together.

The fact that I'm light-skinned with so-called "good" hair (ha!), the fact that I grew up in Tinseltown instead of South L.A. like some of my classmates during the era of school desegregation, the fact that my Black mother never married Black, the fact that I have blond-haired family along with my Black family (and Mexican, Chinese, and Native American family, too) -- all of these facts take nothing away from the equally true fact that I am indeed Black, and Black enough.

MORE FROM OUR RACE IN LA SERIES

- Please Do Not Call Me A 'Mutt' (Not Even You, Mom)

- Connecting Family Stories: A Latina Angeleña Explores Her Deep California Roots

- From 'Go Back To Your Country' To A Vice President-Elect Who Shares My Grandmother's Name

- My Mom Was A Black Entrepreneur. I Never Thought About It, Until Now

- How An Outsider Found Identity, Belonging In The Intangible Shared Spaces Of A Redlined City

- Perspectives on Artsakh from a Black Armenian Angeleno

- Our Heroes Got Us Into This Mess. We Have To Get Ourselves Out

- Surviving The Endless Waves: When American Dreams Aren't All They're Cracked Up to Be

- How A 'Secret Asian Man' Embraced Anti-Racism

- On Race, School, The Teacher Who Tried To Decide My Fate And Those Who Let Me Decide It Myself

- How To Participate In Our Series

We were certainly Black enough to be refused entry at a movie theater in Westwood once. My sister, her Black boyfriend, my twin brother and I wanted to take our young Jewish stepbrother to see a movie that was largely filmed in his mother's house. But it was rated "PG-13" and he wasn't old enough.

The theater manager refused to accept that we were this boy's family, and therefore acceptable guardians. If we had been all Black, or all white, I'm sure we would not have been stopped at the ticket booth.

We decried the blatant racial discrimination and left. My sister's boyfriend was so upset, he got us from Westwood Village back to West Hollywood via Sunset Blvd. in literally five minutes. No exaggeration.

THE SCHISM

Of course, I'm not blind or naïve. I know the unfortunate legacy of associating color with privilege (or lack thereof) among Black people in America. This reaches back to slavery. The "white is right and light is close enough" schism between slaves -- between the so-called "house" N-words and the "field" N-words -- was no accident, in my opinion.

The rape of Black women and the favoritism shown to the white master's offspring were a purposeful added layer of oppression, affecting the psyche of all slaves in the trade's comprehensive effort to sustain a "divide and conquer" strategy. It lasted even after the end of slavery, as we saw in the first decades of the 20th Century with the "brown paper bag test."

Some semblance of what actress Gabrielle Union has aptly called the "us against us" schism remains today. It's been perpetuated in my lifetime by, for example, the entertainment industry that for years featured light-skinned Black women as the standard for Black beauty, or that more often than not has depicted light-skinned brothers as "pretty boys" and darker-skinned brothers as thugs.

The sitcom "Black-ish" bravely dedicated an episode to this phenomenon of "colorism" within the Black community and the resulting perceptions of privilege.

Titled "Black Like Us," the episode gave both the light-skinned and the darker-skinned members of the family in the show the opportunity to share their different perspectives, pain, and concessions on the hard realities of colorism. It was powerful.

ACTIVISM

My personal full embracing of my Black ethnic and cultural heritage really revealed itself in college. During my sophomore year at UCLA, I went into the Black students' newspaper office to see if they needed a writer or proofreader.

When I told a young man why I was there, the first thing he said to me was, "Man, you're so proper -- just like a white girl!" To which I immediately replied, "Well, gosh golly!" He laughed. I laughed. We became good friends.

I have the fondest memories of those years, writing on issues of race and current events of relevance for Black students, developing friendships with people I'm still connected to, and gaining a balance of life lessons from both the classroom and my growing activism.

I marched, helped build a tent city, and joined the occupation of the administration building in protest of South African apartheid.

And just like my grandmother did when she was that age in Detroit, I joined picket lines to protest racial discrimination at places of business in Westwood Village. As a member of the Black Students Alliance (BSA), I helped plan and facilitate special school visits by dignitaries of the time, including Bishop Desmond Tutu, Kwame Ture and Rev. Jesse Jackson.

Then, after my stint with the Black students' paper, I was accepted as an undergraduate representative on UCLA's student publishing board that elected the first Latino editor-in-chief for the Daily Bruin.

AGGRESSION

By this time in my life, I was also developing a thickening skin, albeit still light.

I still had to deal with micro- and sometimes macro-aggressions from my own people, à la the Spike Lee joint, "School Daze." That film is a perfect caricature of colorism among Black college students.

For example, during a campus BSA meeting, one of the leaders quipped that the only reason my mother had achieved her level of success at the time was because she was married to a white man. First of all, my stepdad had no interest in, let alone any ties to, the local television industry. Second of all, he had grown up a victim of bigotry himself, as a Jew in a working class, white Anglo-Saxon Protestant neighborhood in Chicago. And third of all, the brother who said this was lighter than me.

My fellow student leader's words may not have been motivated by colorism against me per se, but it was a shot pointed in my direction nonetheless. Why do we have to belittle or diminish each other in order to feel better about ourselves?

Now, let me be just as quick to say, most of us don't do this. I'm grateful for that, because I'd rather we celebrate and support each other than belittle or devalue our diversity and our collective track record of overcoming the cards historically stacked against us in this country.

This is especially important in today's racially charged society, and it's for the sake of our children and grandchildren.

OVERCOMPENSATION

Growing up, all four of our own caramel-colored kids experienced color-focused aggressions to one degree or another from fellow Blacks, with varying frequency. While it was hard on all of them, I wonder if the fact that my "chosen" daughters (i.e., my two stepdaughters) attended a predominantly Black K-through-8th grade school with pretty much the same kids over the years made any aggressions less pronounced, and therefore easier to deal with.

Because of the expansive range of Black skin tones seen at their Inglewood Unified school every day for eight or nine years, when that's all that the kids were around, the differences could become mundane and insignificant.

But for my two sons, at the suburban schools they attended, they were among only a handful of fellow Black kids in a sea of non-Black faces.

Most of those other Black students were also transplants from L.A. and they all, including my sons, felt the pressure to fit in without losing their "Blackness." So, to avoid being called whitewashed or a sellout, they overcompensated by exaggerating how they talked and what they talked about, how they walked, dressed and behaved, and how they socialized.

My husband and I made that hard choice to move from Ladera Heights to a predominantly white suburb, not to get away from living in a Black community, but because of the economies of the two differing public school systems. There are 10 years between our youngest daughter and oldest son, and by the time he reached third grade, the surrounding residential community had already started putting their kids in private school, which impacted Inglewood Unified School District funds.

Moving where we did meant going from students having to share textbooks to every student getting two sets of books, one to keep at home and the other at school. We would not have moved otherwise and, candidly, we've had some misgivings.

Unlike their sisters, our boys were regularly verbally attacked from both sides of the racial spectrum at their mostly white school and in the community. While they were often called the N-word by white youths, they were also told by both white and fellow Black schoolmates, "Why don't you act more Black?" ("Well, gosh golly!")

We never told them or implied that they should not "act Black" -- whatever that is. We did encourage them to be themselves, which is Black, and to always keep in mind that they represent the Davis family wherever they go and in whatever they do.

Oh, and I insisted they stop using the N-word with their friends, because I don't accept our people trying to legitimize an historically oppressive word that out of any other person's mouth would be offensive to us.

Growing up in the town they did, with macro- and micro-aggressions coming from whites and fellow Blacks alike, our boys get it. They had to, if for no other reason than for their resiliency and self-determination during those critical teen years. They had to get "the talk" about what to do in situations with poorly trained or racist cops, skinheads, or angry white ex-girlfriends.

They also had to be encouraged for those times they felt that their Black friends were more concerned about appearing "down" or "woke" at the expense of just being real with themselves and each other. My sons have mostly Black extended family on both sides, and their dad grew up on 48th and Western, so they could tell who was being authentic and who was fronting.

OVERCOMING

As adults now who have served in the military, where they had to form the strongest brotherhood with some racist counterparts who literally knew nothing about Black folks except what they saw in the movies, my sons appreciate all the more who and what they are.

And whereas they used to get tired of watching yet another Blacks-overcome-oppression movie with their Baby Boomer parents (à la "The Great Debaters," "Remember The Titans," etc.), they realize that they live in a day, age and country where unarmed, young Blacks -- just like them -- are often killed by cops who are trained, but who still can't seem to tell a real threat from their own presumption of one.

My sons don't need to act more Black just to appease some whites who think all we eat is fried chicken, or some Blacks who expect them to talk more 'hood. What they need to do -- and as full adults now, they realize this -- is to watch their backs, be positive role models to their niece (age 17) and nephew (age 4), work harder and smarter in hopes of getting equal opportunities, and help make a lasting difference in other people's lives.

'FREDERICK DOUGLASS'

One Thanksgiving, when both our boys were home on leave, my grandfather called for them to stand in front of him so he could impart some words of wisdom. He was in his late 90s at the time.

He talked to them for a few minutes but I wasn't within earshot, so later I asked my youngest son what his great-granddad had said.

And what was his answer? "I felt like I was talking to Frederick Douglass!" If only!

Seriously, though, I'm glad my sons had that moment. Sure, my grandfather was no Frederick Douglass in terms of influence and international legacy. But he still left a legacy -- his legacy -- as a Black man, husband, father, patriarch, civil rights activist and writer. And that legacy solidifies my Black heritage and, by extension, that of my sons.

It has nothing to do with whether or not my skin is dark enough, or my hair is kinky enough, or my speech is urban enough, or if the places I've lived have been Black enough.

I've been teased that my skin tone throws off the lighting in family photos. But I don't get mad because, if I did, then I myself would be making my skin more significant than it deserves to be. It is what it is, and that's it.

No, it's my genes and my personal family heritage, both of which I am very proud of, that make me what I am. And what I am is more than Black enough.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Laurel Davis is an L.A. native who grew up mostly in West Hollywood. Her passion is writing and editing, and through her company, Empathy Editorial, she loves helping clients say what they want to say better than they can say it themselves. Her own feature stories have appeared in several print publications and online blogs.

Laurel is grateful for this opportunity to share a little about herself and about aspects of Black American history that give context to her personal story. She and her husband, a pastor and fellow L.A. native, have four kids, two grandkids, and four grand-puppies.

-

My good friend used advance parole to leave the country and return. Now it's my turn to go back "home."

-

When you grow up in Anaheim close enough to watch Disneyland fireworks every night while your family can’t afford to go, you can’t help but feel like you’re on the outside looking in.

-

She sat down with us in April, nearly 50 years after the night she turned down Marlon Brando's Best Actor Oscar — which is still among the most memorable and contentious in Academy Awards history.

-

Latin America is no stranger to racism and colorism — just turn on a telenovela and see for yourself. And it’s alive and well in our own communities here in the U.S.

-

When you grow up identifying as "half white and half Mexican," the task of choosing what box to check on a government form isn't easy.

-

Growing up as the son of a Filipino immigrant dad and Russian American mom, Mark Moya felt equally attached to both cultures. He still does. Lately, he's been thinking more about their immigrant legacy and how it shaped him, especially after losing his dad earlier this year to COVID-19.