A Doctor Wrote About Racism As An Elite Athlete. He Wasn't Prepared For The Hate Which Followed

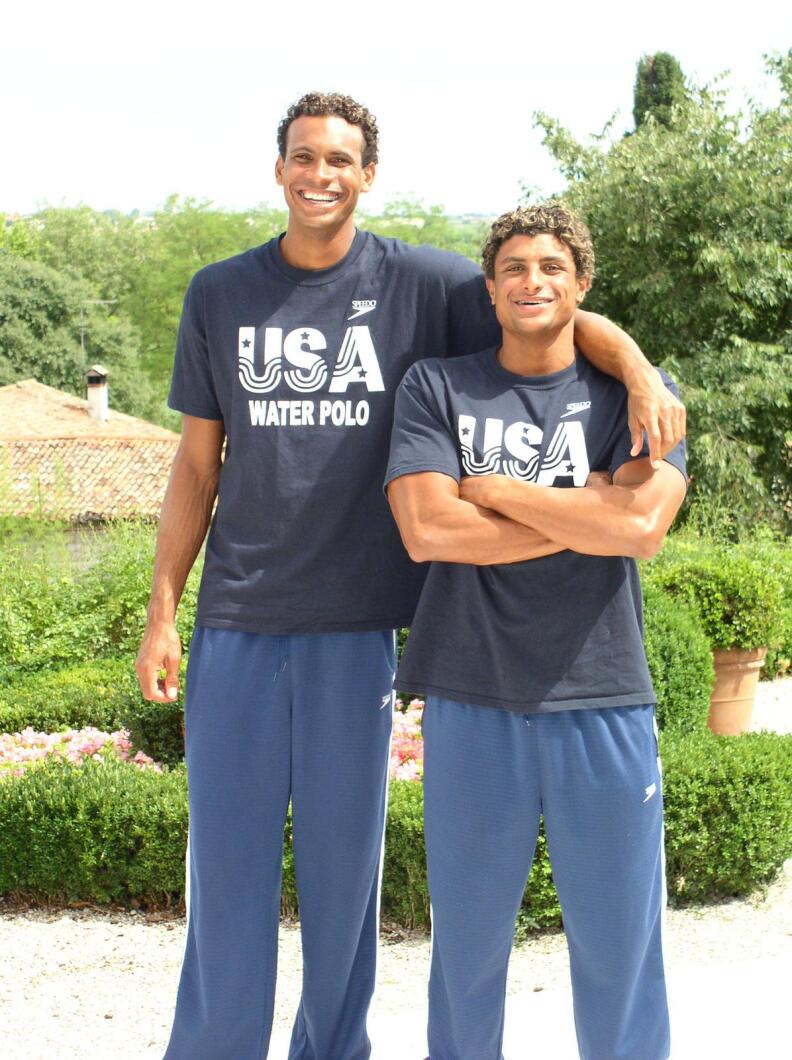

Last May, following the death of George Floyd, I was invited to contribute to Race In LA. As a dark-skinned Egyptian American, I’m technically “African American.” I’ve often been mistaken for Black though I don’t identify as a member of the Black community. I’ve been called the n-word by classmates and neighbors. When I was younger, my father instructed me to keep my hands visible at all times if I was ever pulled over by the police. And, most dramatically, I’ve heard my share of racist taunts, when I was a medical student at Harvard and a member of the U.S. Olympic Water Polo Team. Though I’ve loved — and excelled at — water polo since I was a child, the sport was, and continues to be, largely dominated by white players and coaches. I felt I needed to share my story.

-

From June 2020 to July 2021, we published your stories each week to continue important conversations about race/ethnicity, identity and how both affect our lived experiences. We now have a new series Being American, which is again soliciting your essays.

-

Read:

My essay was published in September, and it was quickly picked up by several other media outlets, including CBSLA and The Olympic Channel. I found myself thrust into the spotlight in a way I’d never fully intended. I’d wanted to raise awareness about the need to diversify my sport and to help people who’d faced similar experiences feel less alone.

The governing bodies involved in U.S. aquatics and Olympic sports largely ignored my call for reforms for racial and gender equity prior to the publication of my essay. When I’d played water polo competitively, it wasn’t uncommon for me to hear the n-word from opposing white players in the pool. Within days of publication, however, a task force was formed which enacted a “zero-tolerance policy.” However, specific details of what the policy covers and how it will be enforced have yet to be released.

ICYMI, 2004 Olympian Dr. Omar Amr shared his journey to an Olympic dream with @LAist. Amr chronicles the racism he faced both in and out of the pool on the way to become an Olympian and and a doctor.

— USA Water Polo (@USAWP) September 14, 2020

MORE: https://t.co/3y6trfxFnD

I never envisioned that my essay would become a commentary on race in America or that I would wind up on TV. I also didn’t expect to lose some of my closest friends.

Unexpected Backlash

While I received hundreds of kind messages from my family and friends, I received far more messages of hate and more than a few death threats. Some of these angry missives came from old friends I hadn’t seen or spoken to in decades. And, most heartbreakingly, a few of my former teammates. These were dear friends I’d played water polo with since I was a teenager, guys I’d once lived with and traveled with in pursuit of our shared Olympic dreams, who accused me of lying in my essay and insisted that, despite my experiences, racism in water polo didn’t exist. One teammate refused to talk to me about some of our past interactions; another questioned my mental health, suggesting I must have been unbalanced to publish my essay.

Another teammate, one of my oldest friends, insisted racism couldn’t exist in water polo because he’d worked with minority outreach programs in his hometown. The fact that he’d taught the sport to kids of color was proof of our sport’s enlightenment. He’d been a strong ambassador for the sport, and I told him so, but my experiences hadn’t been the same as his.

“Polo gave you everything you have today,” he told me. “Complaining this way is like biting the hand that fed you.”

“I’m not complaining,” I said. “I just wanted to call attention to the issue.”

He wasn’t convinced. He agreed with others that I might be mentally ill. They questioned my intelligence and wondered publicly how I could be a doctor.

Though several months have now passed, these teammates and I still haven’t spoken to each other. I think about them almost daily, and miss them. And I’m disheartened by the extent to which racism is ingrained in American culture.

Being Heard Versus Being Believed

For people of color, talking about racism can be almost as hard as experiencing it. It’s not because the topic itself is traumatic but because it’s often so hard to convince people who haven't experienced racism for themselves that racism is real. It can be hard to believe that the same police officer who kindly stops to help a white family change a flat tire can also pull a gun on a dark-skinned mother and her son over a parking violation, as a cop did when I was 12. In my experience, whenever a person of color tries to talk about racism, they’re often accused of exaggerating or outright lying, of being “angry,” “militant” or “uppity.” When we try to discuss racism, we have an ax to grind or a chip on their shoulder and are filtering everything through a lens of race.. To that, I say:

It’s hard not to see the world through a racialized lens when everywhere I go people perceive and judge me based on the color of my skin.

During my time in medical school and as an elite athlete, I noticed that people of color often seem to find each other. We gravitate toward one another across crowded classrooms, locker rooms, corridors and cafeterias. There is, of course, a reason for this: There is safety in numbers and one is, as the song says, the loneliest number. I appreciate my many white friends who have offered their support and sympathy. But, until they start believing stories of what it’s like to live in a dark-skinned body, I fear that both racism and, ironically, the denial that racism is real, will persist. In some respects, the problem seems to be getting worse.

I live in Huntington Beach, an old surfing town known mainly for its laid-back vibe and annual surf contest. Two weeks after George Floyd’s death, there was a Black Lives Matter protest in town. Initially, I was cheered by the event: The death of an unarmed Black man 2,000 miles away was igniting demands for racial justice in my hometown. Yet, the BLM march was greeted with a shocking counter protest of nearly equal size. A parade of Confederate flags and posters with swastikas flooded the streets and chants of, “All lives matter!” — a rallying cry that only underscores the fact that Black lives so often aren’t considered part of “all” lives — filled the air.

As I watched the protesters march down the street, I felt sick to my stomach. The more people work to take down the barriers of racism, the stronger those barriers seem to grow. However, standing there on the street, I also had another thought. These racist demonstrators are an embarrassment, but at least they’re honest about what they think. The harder problem to solve is what I sometimes think of as “covert racism” perpetrated by those who don’t think racism is real, who believe racism in America has been “solved” because a Black man once served as president, because they’ve donated money to an organization “that supports equality,” because they have coworkers or friends of color. I often find myself wanting to ask, “How seriously do you listen to your BIPOC friends? Do you make space for them to talk about their experiences? Do you believe them?”

After my essay was published, I received a call from a former teammate who told me he’d read what I’d written and wanted to offer his support. I was grateful and thanked him for calling. Later that afternoon, I was notified by the CEO of USA Water Polo that the same person, the same guy who’d reached out to me, had called the organization to discredit me and my essay. He was willing to come forward with other teammates to prove I lied. Ultimately, it came down to their word against mine. I was, once again, the outsider. I began to feel depressed.

For people of color — especially water polo players of color — the reaction to my essay was quite different. Many asked to talk to me directly but wanted to remain anonymous, fearing, I surmised, the same negative reactions I was receiving. They told me stories of being called racist names, being excluded from team meetings, humiliated in public. One athlete told me that while training with the national team, another player carved his name onto his arm and told him to call him “master.” He had the scar to prove it. Their stories broke my heart.

Racism Is Pervasive

The protests for and counter protests against racial justice, of course, are not the only hurdle America has faced in the last year. The COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged the country — and the world. As an emergency medicine physician, I have borne witness to more death in the last year than I have in the previous 10 (and I’ve seen my share of gunshot wounds, horrific car accidents, heart attacks and domestic abuse). I have personally seen how the pandemic has disproportionately affected communities of color, whose people often live in more crowded homes, earn less money from less stable jobs and have higher rates of underlying medical conditions. My personal observations are supported by research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Yet, amazingly, the Journal of American Medicine (JAMA) — by all accounts, the most respected medical journal in the country — recently released a podcast on structural racism in which two high profile white physicians argued that structural racism could not exist in medicine because, in their words, “No physician is racist.” Racism, the doctors argued, has been “illegal” since the 1960s and that the problem instead was socioeconomic. The podcast, mired in controversy, was taken down by JAMA and an apology posted in its place. The editor-in-chief of JAMA was placed on leave in the fallout weeks later. Still, I wish their conversation were an anomaly, an outlier.

Almost, daily I overhear other physicians, my own colleagues, dismiss the possibilities of structural racism, deny their own implicit biases, and, as a result, fail to empathize with the very communities they, in other contexts, claim to support. Though medicine is a science, it’s also personal. It relies on honest, empathetic and trusting communication between a provider and a patient. Patients depend on their doctors not only to help them heal from their ailments and injuries but to see them as individual people. To believe them. How can physicians help their patients if they lack the cultural and racial knowledge — about the very real stresses, mental illnesses and chronic health conditions caused by persistent discrimination — to allow them to empathize? How can doctors heal patients if they don’t believe their patients are sick in the first place?

When I first set out to tell my story, I’d never worried about retaliation. I never thought about hate mail or death threats, and I certainly never expected to lose my relationships with friends I considered my brothers. I never considered the possibility that they wouldn’t believe me. We’d gone to battle together, for our country. I expected that fact, our common history, to see us through. Somewhere, in the corner of my heart, I still believe change is possible. I hold out hope that my old friends, my teammates, will one day be my friends again. But in order for that to happen, they’ll have to believe what I’m saying and accept that though we once wore the same uniform and competed for America, my experiences were different from theirs. All they have to do is believe that I’m the honest person they’ve known for decades. In the meantime, I refuse to be silent. I’ll keep telling my story.

-

Dr. Omar Amr is a Harvard-educated emergency medicine physician who has been practicing for 14 years. He is now the ultrasound director of a residency program he helped start at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton. While attending Harvard Medical School, he also competed in the 2004 Olympics for Team USA. Most recently, he founded the Alliance for Diversity and Equity in Water Polo. The ADEWP fights for equal opportunities for BIPOC athletes and works to prevent discrimination and promote inclusion within the sport.

-

My good friend used advance parole to leave the country and return. Now it's my turn to go back "home."

-

When you grow up in Anaheim close enough to watch Disneyland fireworks every night while your family can’t afford to go, you can’t help but feel like you’re on the outside looking in.

-

She sat down with us in April, nearly 50 years after the night she turned down Marlon Brando's Best Actor Oscar — which is still among the most memorable and contentious in Academy Awards history.

-

Latin America is no stranger to racism and colorism — just turn on a telenovela and see for yourself. And it’s alive and well in our own communities here in the U.S.

-

When you grow up identifying as "half white and half Mexican," the task of choosing what box to check on a government form isn't easy.

-

Growing up as the son of a Filipino immigrant dad and Russian American mom, Mark Moya felt equally attached to both cultures. He still does. Lately, he's been thinking more about their immigrant legacy and how it shaped him, especially after losing his dad earlier this year to COVID-19.