The Hidden Cost Of Inherited Blackness

Our news is free on LAist. To make sure you get our coverage: Sign up for our daily newsletters. To support our non-profit public service journalism: Donate Now.

My father was born 12 days before Emmett Till. July 1941 was an inauspicious time to be young and Black in America. When the two, round-faced baby boys came screaming into the world, they knew no color, and yet, the nation's perception of theirs was already destined to shadow them from cradle to grave.

A month after his 14th birthday, Young Emmett was beaten and killed for being the wrong color in the wrong place. Two hours north, my dad, Young Thomas, heard the news. He was unphased.

-

From June 2020 to July 2021, we published your stories each week to continue important conversations about race/ethnicity, identity and how both affect our lived experiences. We now have a new series Being American, which is again soliciting your essays.

-

Read:

"People of color didn't have any rights back then. You were a boy or the n-word, or you were nothing," he'd say.

It could have been either of them, really. He knew it. All his friends knew it. But they carried on.

"You just took it in strides," he'd say. "That's the way it is. It couldn't get better."

That was the philosophy that kept Black people safe, he told me: accept that it's not your world. Work with the system. Play the game. Do the best you can to ensure that your kids will have to deal with a little less of the bullshit.

MORE FROM OUR RACE IN LA SERIES

- Jogging While Black: 'And Still They Crossed The Street'

- Black And Tired In This American Newsroom

- Conflicted: A Black Journalist's Reckoning With Her Race, Family And Police Brutality

- How To Participate In Our Series

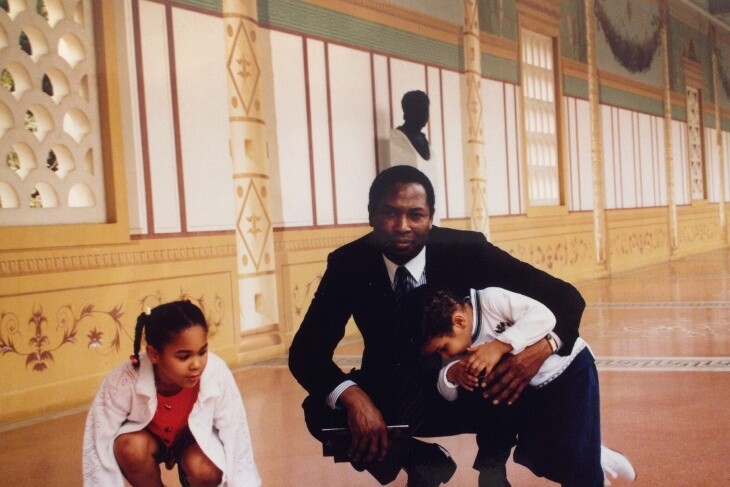

My father taught me the rules of being Black in America. Many of his younger years were spent in the Jim Crow south. He came to Los Angeles just in time to be greeted by the Watts riots. When he lost count of how many times he'd been pulled over while driving down Wilshire Boulevard, he started dressing in a suit and tie. He figured the LAPD wouldn't bother him if they thought he was a chauffeur. The pullovers stopped. He wore a tie until the week he died.

Since the death of George Floyd at the hands of those Minneapolis police officers, I've thought a lot more about what my dad taught me. The omnipresence of race in our news cycle paired with the unstructured hours of quarantine has led me to realize the extent to which his advice has seeped into every aspect of my thought process. His guidance extended far beyond the oft-repeated "hands on the steering wheel" rule.

It factored into the way I dress: Always be presentable. Hair combed. Shirt tucked-in.

Into the way I speak: People won't listen if you don't sound educated.

Into my demeanor: Calm, pleasant, and direct.

Even into how I think about those who look just like me: "I hope they don't make me look bad."

My father no longer lives, but, I'm chagrined to report, that his time-tested philosophies remain alive and well in me. It's like the inheritance I never wanted, but also kind of need every day. It was delivered in pieces over the course of 30 years with no receipt. What can I say? Thanks. I hate it.

The most twisted part about this philosophy, I've found, is that if a person of color gets hurt, they're somehow at fault for not playing the game properly.

For example, some insinuated Ahmaud Aubery was killed because he had stopped by an unfinished house.

The lesson that me and many like me are hardwired to take from this? He probably shouldn't have hung around.

Then came George Floyd, who died after an officer applied pressure to his neck for nearly nine minutes for allegedly spending a fake $20 bill.

The lesson there? I'll take "Dress nicely so people don't assume you're up to no good" for 500.

God.

After more than 30 years of playing by the rules my father taught me, I understand just what I have inherited: an antique set of rusty shackles.

Safety is just the bi-product of following these unwritten commands. The rules ingrained in me are merely an inversion of the regulations imposed on my ancestors by a system designed to keep us obsequious to White supremacy from the moment we stepped off the boat. Slavers encouraged these rules so that we would regulate ourselves.

It's the same system, I realize, that gave us respectability politics: one of the few pathways available to Black people hoping to take their seats at the far end of the economic table. My father knew this system well. He learned how to play the game. You might even say he won. But frankly, I'm tired of taking part in a system that only rewards those willing to shed their identity.

If everything I have to do in order to survive is for the comfort of others, what have I left for myself? What is real?

Since my dad passed, I've spent a lot of time reflecting on why I am the way I am. Last week, I asked my mom about my dad's views on race. I mentioned his apparent indifference to the death of Emmett Till. She told me a different story.

When Till's body was discovered, beaten, and mangled that August day in 1955, my dad was scared. His mother was scared. His whole damn community was terrified. He just said he wasn't so that I wouldn't be.

And there it was, clear as day, like a primordial atom from which our collective psyche flows: To be Black in America is to live in constant fear.

We must break these invisible chains before another generation of Black children inherits the scars of their forefathers. Before another young man puts on a necktie, hoping it will function as a bulletproof vest. It's on me, and it's on you.

The great activist James Baldwin once said that "not everything that is faced can be changed." But he added that "nothing can be changed until it is faced."

Today, we're facing down a system that binds the hands of every Black American. What will you do?

-

My good friend used advance parole to leave the country and return. Now it's my turn to go back "home."

-

When you grow up in Anaheim close enough to watch Disneyland fireworks every night while your family can’t afford to go, you can’t help but feel like you’re on the outside looking in.

-

She sat down with us in April, nearly 50 years after the night she turned down Marlon Brando's Best Actor Oscar — which is still among the most memorable and contentious in Academy Awards history.

-

Latin America is no stranger to racism and colorism — just turn on a telenovela and see for yourself. And it’s alive and well in our own communities here in the U.S.

-

When you grow up identifying as "half white and half Mexican," the task of choosing what box to check on a government form isn't easy.

-

Growing up as the son of a Filipino immigrant dad and Russian American mom, Mark Moya felt equally attached to both cultures. He still does. Lately, he's been thinking more about their immigrant legacy and how it shaped him, especially after losing his dad earlier this year to COVID-19.