Rent control can either be your friend or your enemy.

The laws are often the bane of landlords who’d like to charge more and a potential safety net for tenants who can’t afford steep rent hikes. But why it’s around isn’t necessarily because politicians want to protect the little guy — rent control has historically been used to mitigate another problem.

-

How much can rent go up in my neighborhood?

- Read our rent control guide to find out how much your rent can be legally increased each year, depending on where you live in L.A. County.

If you want a breakdown of how rent control may work in your area today, here’s the guide for that. But in this one, we’ll explore more of the backdrop: how high inflation, wartime efforts and a housing crisis birthed different eras of rent control.

The wartime effect

L.A.’s first round of modern rent control came more than 80 years ago — and it was perhaps the strictest we’ve seen.

When World War II began in 1939, industrial employment ballooned. The Great Depression was easing, so workers migrated to Los Angeles in the tens of thousands for employment. But the surge in population, combined with the war effort, created a perfect housing storm that lasted for years.

More people were coming at a time when our housing stock couldn’t keep up. About 15,000 residential projects went unfinished because labor and supplies were diverted to the war, according to research from the UCLA Luskin Center. With demand way up, many people had no choice but to live in severely overcrowded and unsuitable conditions. The situation was so dire when a federal study was conducted that a veteran shared how he was living in a house with 18 other people while trying to turn a chicken coop into a place to stay.

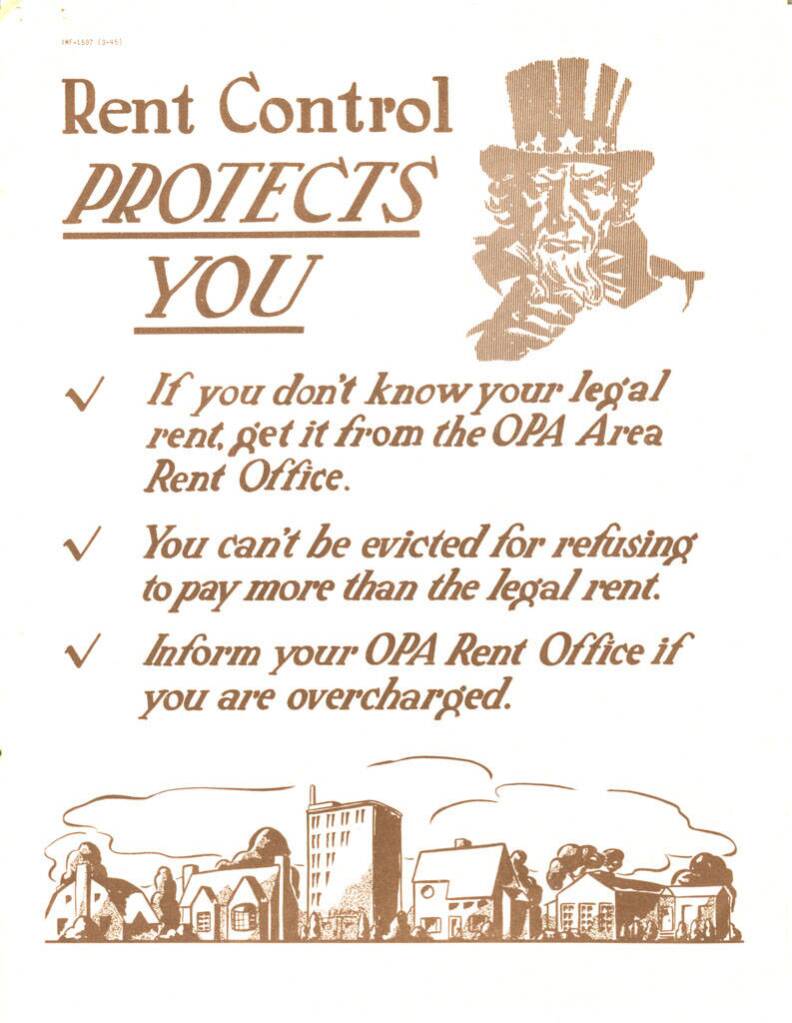

The ultimate solution would be more housing, but that would take years to improve. In the interim, the federal government deployed a rent freeze (and other price controls) in 1942 to ensure essentials remained affordable. Alisa Belinkoff Katz, lead author of UCLA’s study of rent control in L.A., says this move made rent control part of the war effort and more acceptable to landlords.

“It was considered sort of the patriotic thing to do, at least at first while the war was going on,” she said. “It became something that was widely publicized and that people were engaged in.”

That publicity campaign helped to make tenants aware of their rights. Landlords and renters were also required to sign a property registration form that recorded the rent amount under the freeze. To Katz, the tenants who kept tabs on compliance, along with federal enforcement, is what made the rent freeze effective.

The support of landlords didn’t last long, though. The L.A. County apartment association’s president at the time, David Culver, complained about treatment in a meeting with landlords, and together they vowed to take action. They argued that the rent cap was too low to afford taxes and maintenance, and some threatened to take their rentals off the market.

Once the war ended, rent control became a ticking clock. After a postwar federal housing act went into effect, allowing local governments to lose the rules, the L.A. City Council voted to decontrol. Residential rents went back under the sway of the market.

‘Stagflation’ in the 1970s and Proposition 13

Decades later, L.A. was in a different predicament.

An oil crisis was going on, aiding a surge in inflation while economic growth was at a snail’s pace. This is when the term “stagflation” was coined (a portmanteau of stagnation and inflation). Among a number of other things that became more expensive, L.A. home prices were skyrocketing along with owners’ property tax bills.

Landlords again organized around this issue. Howard Jarvis, then-executive director of the L.A. County apartment association, went down in history as the champion of 1978’s Proposition 13 — a measure that aimed to cap property tax rates. But in order for it to pass, he knew that the state’s renters — which made up 45% of households, according to Katz’s research — needed to be convinced to vote for the proposition.

Landlords got involved to persuade their tenants. They argued that getting their tax bills reduced would trickle down to their tenants, too. Some even offered rent rebates if it was successful. But after Proposition 13 prevailed at the polls, the rose-colored glasses fell off. Despite what they’d said previously, many owners continued to raise their rents — some by more than 20% that same year.

“It should be an incentive to keep rents low, one would think,” Katz said. “But it hasn't worked out that way because property values continue to rise all over the city. [It helps landlords] because their taxes aren’t going up. So if their taxes are stable and their rents are allowed to increase all the time, then of course it helps them.”

In effect, the law was a type of rent control but for landlords, because it lowered their property taxes and limited increases.

Renters feeling the pinch

Demand for tenant protections was high in this decade, especially in middle-class communities. Renters had few rights and people were feeling the pinch.

“Our phone started ringing off the hooks,” said Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival. “It appeared that the speculators discovered Los Angeles. They were buying up rental units throughout the area, raising rent, putting a fresh coat of paint on it, some minor repairs, and then selling it again."

Gross was one of the key people leading the fight for rent control and helped organize tenant unions. He says some apartment buildings were getting flipped four to five times a year. And after Proposition 13, he says the “lid blew off” with rent.

It was the first of many broken promises that landlords provided to their tenants.

“It was the first of many broken promises that landlords provided to their tenants.”

Renters rallied, urging L.A. leaders to take action. The city council members who represented white, middle-class districts supported the measures, but the ones leading Black and Latino districts did not. Back then, rising rent was viewed as a middle-class problem, and community leaders in lower-income districts worried that rent control would drive away investment in their communities.

Still, the council got enough support to roll back and temporarily freeze rents. Mayor Tom Bradley claimed it was a necessary step to halt “outrageous rent increases.”

The freeze gave the council time to draft a long-term response, which is where the Rent Stabilization Ordinance in place today came from. With this law, landlords can only increase rent in certain properties (built on or before Oct. 1, 1978) generally between 3% and 8%, based on inflation. (There’s a rent freeze on these properties currently because of COVID-19.)

Where we are now

Since the '70s, a lot has changed. Rent control has grown to multiple cities, but so have the legal battles surrounding it.

“It's literally been somewhat of a cat-and-mouse game with landlords,” Gross said. “Because landlords will find loopholes in the law and then use that to evict tenants or increase rent. And then we'd identify those loopholes and we get the city council to close them.”

Property owners looked to change these rules, too, and they got key laws passed from higher up.

New rent laws

1985: The Ellis Act, a California law that allows landlords to evict residential tenants in order to leave the rental business, passes. A landlord filed a lawsuit against Santa Monica, which instituted rent control six years earlier, for refusing to let him demolish his rental property, claiming it was in bad repair. He lost the case when it reached the California Supreme Court, but shortly after the state legislature passed the Ellis Act.

1995: The landlords’ grand slam, the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, passes. This was the state legislature’s response to landlords' building frustration with rent control laws, which were more regulated in some cities.

West Hollywood and Santa Monica, had the strict “vacancy control” rule. Under that provision, owners couldn’t raise rents to market rates between tenants, but small increases were allowed during tenancy. The act made that provision illegal statewide.

It literally puts a bullseye target on the back of particularly low-rent, long-term [rentals].

“It literally puts a bullseye target on the back of particularly low rent, long-term [rentals],” Gross said on the removal of vacancy control. “If they get those tenants out by any means, they can jack up rents to whatever they want.”

The act also prohibited rent control on residential properties built after Feb. 1, 1995, excluded single-family homes and condos, and generally tied city leaders' hands.

“It froze existing local rent control laws,” Katz said. “It had a huge impact because it prohibited what local governments were able to do to protect renters in their jurisdictions.”

2019: The Tenant Protection Act created a statewide rent increase cap. This cap is adjusted yearly based on inflation. It’s intended to prevent very large increases. And, coming soon, California will be voting on rent control in 2024 (for a third time).

Navigating rent control

It can be tough to easily understand how, when, and where rent control affects you. Everything can change depending on what city you’re in, your building type and when it was built.

Some basics you should be aware of are the main types of rent control:

- Rent freeze (rents are not allowed to rise at all in a given period).

- Vacancy control (rent can’t rise to market rates between tenants, but smaller increases are allowed during tenancy — this is illegal in California).

- Vacancy decontrol (rents can rise to market rates between tenants, and increases are allowed during tenancy — the standard in the state now).

Another way that rent control can change is with how much of the consumer price index, which measures inflation, gets factored in.

For example, the city of L.A. typically lets rent controlled properties increase between 3% and 8% a year, depending on the full rate of inflation. But Katz says that other cities have used a lower percentage of CPI. And the city of L.A. has a freeze on increases in rent controlled buildings until February 2024.

Cities with floors for increases, like L.A., can wind up with a problematic deal for renters and a better one for landlords if rents rise above CPI.

“Several times in the last few years, CPI has actually risen less than 3%, but landlords were allowed to raise the rents by 3%. So that's another question, whether that should be adjusted," Katz said.

Figure out where you stand

Rent control is a tangled web of seemingly boring rules, but it does have real effects. To supporters of the protections, the aim is about keeping things affordable and fair.

“It helps to give some security to tenants in a sense that it extends the protections that homeowners have,” Gross said. “What rent control does is level the playing field.”

If you're a renter and would like to know more about where your home stands with rent control, check out my colleague David Wagner’s cheat sheet to rent hike. If you’re in the city of L.A., you can also put your address into ZIMAS and check the housing tab to see what laws apply.

-

The city passed a law against harassing renters in 2021. But tenant advocates say enforcement has been lacking.

-

The Emergency Rental Assistance Program will provide up to three months of support to families with unpaid rent or at risk of becoming unhoused.

-

Now that L.A. officials know who landlords are trying to evict, city workers are showing up at renters’ doorsteps to offer help.

-

Allowable rent hikes depend on where you live, and in what type of building. Here’s your guide to figuring it all out.

-

The council approved a hotly debated proposal to lower allowable rent hikes in most of the city’s apartments from a maximum of 9% to 6% in February.

-

The vibrant neighborhood crams 700 restaurants into a roughly two-mile radius, while many workers cram themselves into overcrowded apartments.