What It Really Means To Amplify Black Voices

Our news is free on LAist. To make sure you get our coverage: Sign up for our daily newsletters. To support our non-profit public service journalism: Donate Now.

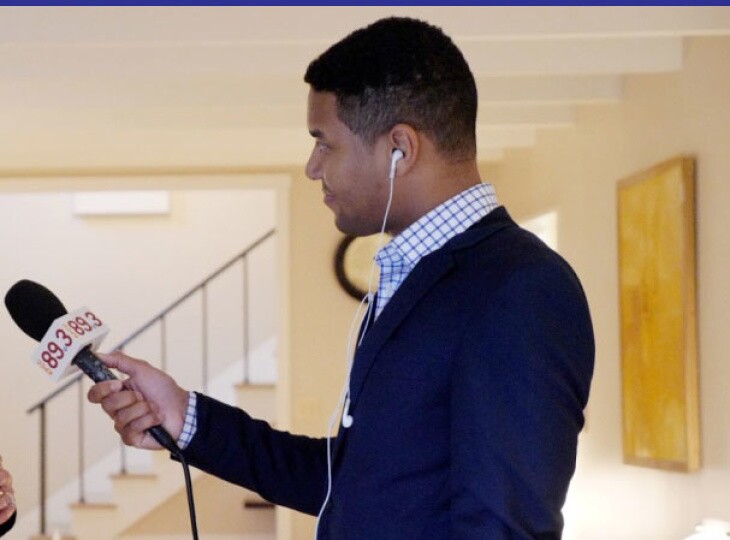

I was on KPCC's Take Two news talk show for less than two weeks when I produced my first conversation about race in Los Angeles. It was April 2015: one hell of a time to wade into the debate over race and policing. But it was also the month that I learned what it truly meant to amplify Black voices.

On April 5, Walter Scott, a Black man in South Carolina, was shot in the back by Michael Slager, a White police officer; the heinous execution was captured on camera for the world to witness. Less than two weeks later, 25-year-old Freddie Gray died in the custody of Baltimore police after a so-called "rough ride" resulted in injuries to his spinal cord. The uprisings that followed shook Obama's America and reminded even the most naive of us that a racial reckoning was long overdue.

-

From June 2020 to July 2021, we published your stories each week to continue important conversations about race/ethnicity, identity and how both affect our lived experiences. We now have a new series Being American, which is again soliciting your essays.

-

Read:

Enter me: A fill-in producer fresh out of news radio powerhouse KNX1070. Less than a week after I was laid off in a round of budget cuts, I went from a legacy newsroom with 30-year employees and 30-second news holes to a comparatively newer house of journalism with 12-minute segments and more millennials than I could count. I relished the opportunity to help Los Angeles have some much-needed talks about race. But it hasn't been easy.

As the third Black person on the team, I had some great mentors in Joanne Griffith and Stephen Hoffman. Each of us carried a unique perspective on the Black experience. But in those first few weeks, I felt that my segments about race were embarrassingly basic. There's no other way to say that.

Even when I received kudos from our predominantly White leadership, their idea of a productive conversation often felt very different from my own. Deep down, I knew that the impact of any segment about race was almost entirely determined by the extent of my own knowledge and reflection on the subject. How could I "go there" if I didn't know where "there" was?

I started easy: a conversation about the use of the word "thug" when talking about Baltimore protesters with a young Jamelle Bouie. That same show, I produced a roundtable featuring a Black professor and a Black community leader from the city. A journalist, an academic, and a faith leader. How do I say this? Sigh.

In times of racial strife, the obvious decision for every outlet should be to "amplify Black voices." The difficult question that invariably follows is: "Which ones?"

In the beginning, I, like many journalists, fell into a familiar media trap. I chose to put a microphone in front of the Black community's polished gems, rather than its uncut diamonds. Subconsciously, I thought I was doing my people a favor by presenting its most assimilated voices. This was my takeaway after four years in commercial news. But if truth and accuracy are the foundation of true reconciliation, then accurate representation is non-negotiable. All Black experiences matter.

As April wore on, the news industry's dearth of nuanced coverage became increasingly apparent. I realized that I would have to become my own critic and develop a mental rubric for booking guests and writing interview questions that were free from the vestiges of inherent white supremacy.

Over the next month, I took listeners along on my personal journey. I produced a discussion about the often-problematic reporting around the Baltimore unrest. UCLA Dean of Social Sciences Darnell Hunt called out the news outlets that focused on the crimes committed during the protests rather than the frustration behind them. The goal was admittedly subversive: I wanted people to understand that those who create the narrative hold the very reins of social change. In retrospect, the conversation was for my own edification as much as anyone else's.

The turning point in my production work came in August. Longtime NAACP chairman Julian Bond had died. I was tasked with producing a roundtable discussion about the state of Black leadership in America. It was after nearly a week of production that I reached the limits of my own understanding.

So I got on Twitter and just started DMing Black people -- all kinds of Black people. Some days, I did nothing but talk to Black people. I called up activists, asked open-ended questions, and then I sat back and listened. It was commentator Jasmyne Cannick who got me thinking the most during this time.

"There is a huge disconnect from the folks who the media calls on as representing Black people and how Black people actually feel about those people who are out there claiming to represent them," Cannick explained on the phone with me and later on the air.

In the end, Cannick proved to be the right voice for our radio panel. What resulted was a frank discussion about the past, present, and future of Black leadership.

Though the segment existed for just shy of 15 minutes on the air, it gifted me with three lessons that I now use to measure all coverage of the Black experience.

Lesson 1: Times change.

Black people in Black spaces are having conversations about race that never make it to the mainstream media. They're discussing and dissecting social and economic dynamics that would likely sound foreign to more than half of the country. Failure to stay in the loop inevitably results in shallow coverage -- the journalistic equivalent of AstroTurf. Some listeners can't tell the difference, but Black people can.

Lesson 2: Let the story tell you how to tell it.

In the world of broadcast news, time is at a premium. The environment rarely lends itself to amplify Black voices. Finding the right voice takes time. Listening to that voice in a non-exploitative way takes time. Rewriting your entire narrative to reflect the fullness of the story takes time. Breaking out of colonial structures and power dynamics takes time. In this way, I believe, a news organization's dedication to Black lives can be accurately measured by the time they allow their journalists to pursue the stories of Black people.

Lesson 3: Love Black people.

The final lesson incorporates all lessons. I consider it my Golden Rule. Loving Black people doesn't mean giving them special treatment. It means giving their voices the same respect we've historically given to the police. It means respecting Black anger. It means celebrating Black intersectionality. It means recognizing Black individuality. And yes, it means hiring, training, and retaining Black talent.

Five years later, I can say that I'm still learning how to amplify Black voices. Mastery will always be just out of reach. But during this time, when the voice of Black America is too loud for any newsroom to ignore, it is my prayer that the practice of journalism will not emerge from this chapter unchanged and that we too will become part of the history we write.

Correction: A previous version of this story said Darnell Hunt was a dean at USC. He is a professor and dean of social sciences at UCLA.

MORE FROM AUSTIN CROSS:

MORE FROM OUR RACE IN LA SERIES

- Raising A Black Boy In America When You're Neither Black Nor American

- On Life As A Freckle-Faced, Redheaded, Mexican American From Southeast Los Angeles

- Lessons Learned While Being Black: 'I'll Never Be Above Scrutiny'

- Jogging While Black: 'And Still They Crossed The Street'

- Conflicted: A Black Journalist's Reckoning With Her Race, Family And Police Brutality

- How To Participate In Our Series

-

The severe lack of family friendly housing has millennial parents asking: Is leaving Southern California our only option?

-

As the March 5 primary draws closer, many of us have yet to vote and are looking for some help. We hope you start with our Voter Game Plan. Since we don't do recommendations, we've also put together a list of other popular voting guides.

-

The state's parks department is working with stakeholders, including the military, to rebuild the San Onofre road, but no timeline has been given.

-

Built in 1951, the glass-walled chapel is one of L.A.’s few national historic landmarks. This isn’t the first time it has been damaged by landslides.

-

The city passed a law against harassing renters in 2021. But tenant advocates say enforcement has been lacking.

-

After the luxury towers' developer did not respond to a request from the city to step in, the money will go to fence off the towers, provide security and remove graffiti on the towers.